In this issue:

Trolley Problems in the Metaverse

The double-edged sword of DeFi

Lessons from the Death of Diem

Trolley Problems in the Metaverse

One of the compelling things about transformative new technologies is how they force us to re-examine and parse our moral intuitions more carefully. Consider the ethics of self-driving cars, for example. Imagine this scenario:

Late at night a drunk driver returning home from a bar turns on their self-driving car’s autopilot and falls asleep at the wheel. A pedestrian, equally drunk, jaywalks across an intersection during a green light and is struck by the self-driving car and killed. The car was driving faster because it was set to ‘assertive mode’ — a feature the CEO insisted was ready to ship over the objections of the engineering team, but the actual cause of the accident was a bug written into the software by a junior engineer without adequate code review.

When drivers were human we knew who was accountable for a car’s movement and what kinds of conditions it was fair to expect them to successfully navigate. As drivers become algorithms our assignment of responsibility will shift. Likely we will start to treat cars more like we do airplanes, where we place a higher level of trust in the autopilot and a higher degree of responsibility on the manufacturers. But that transition won’t be smooth and orderly — there will be lots of car crashes and lawsuits along the way.

Finance is another area where stakes are high, responsibility is sometimes blurry and technology is redefining the distribution of control and responsibility. Blockchains grant end users greater control but also assign greater responsibility. Being your own bank means more freedom but also fewer people to sue when things go wrong. Imagine this scenario:

A user lists an NFT for sale on OpenSea and then after a while decides to lower the price. Canceling the original listing would require a transaction so to save fees OpenSea and the user leave the original listing in place and simply add a second, lower listing. Later the user decides not to sell the NFT, but now that requires two cancellations and will use twice as much gas, so instead they send the NFT to a different wallet. OpenSea no longer shows the inactive listing anywhere in their UI. Months later having forgotten the listing entirely the user transfers the NFT back to the original wallet and the listing silently reactivates. The months old price is now way below market value and as soon as the listing is discovered the NFT instantly sells for much less than it is actually worth.

Unfortunately this situation is not a hypothetical.

In a traditional market the exchange can intervene in bad trades — either by blocking them from happening or rolling them back. OpenSea however is non-custodial, which means they don’t actually perform any trades themselves — users hold their own assets and trade directly with each other. OpenSea is more like a matchmaking service than a traditional exchange. They have no ability to cancel a listing on a user’s behalf or undo a trade once it has been processed by the network.

On the other hand OpenSea clearly does bear some responsibility here. They designed the listing contracts on the blockchain and the UI users used to create them. OpenSea made listings permanent by default1 and made the decision to hide old listings in the UI even though they were still active on the blockchain.2 Users were signing bad contracts but it was on the basis of OpenSea’s bad advice. Unfortunately they also sent out bad advice about how to fix the issue:

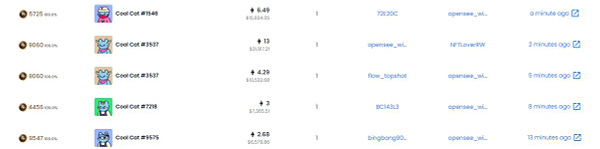

The question of how to assign responsibility for this family of problems is not an abstract one — one of the most successful accounts exploiting this issue is named opensee_will_refund_ask_them. The account is not entirely wrong — OpenSea has refunded at least 750 ETH (~$1.8M) as compensation for at least 130 stolen NFTs. Justice aside there are obvious PR and customer satisfaction reasons to refund affected customers, but even then it is not easy or obvious how to do that.

For one thing it is entirely possible for a user to create a new account and then use it to "exploit" themselves, collecting the sale price with the new account and the refund in the original wallet. For another it is not at all clear how to calculate the fair market value of a non-fungible token, which is (by definition) unique. Do you estimate it at the floor price of the collection? Using its rarest trait? Last sale price? Justin Bieber drastically overpaid for his ape because he wanted #3001. If he is the victim of an exploit, how should his refund be calculated?

The double-edged sword of DeFi

Knifefight, I read an interesting thought the other day that the real flippening will be when on-chain USD flippens ETH. I would be interested in your analysis! - ZM

We’ve talked before about miner extractable value (MEV), the catch-all term for anything miners can do to capture revenue from users. All networks have miner extractable value or they would not have miners (or validators in proof-of-stake networks). But not all MEV is equally healthy for the network.

Miners provide security to the network, but the relationship is a complicated one. The resources and capacity necessary to secure the network are exactly the same as the resources and capacity necessary to attack it. Networks are not secured by how much revenue the miners earn, they are secured by how much more revenue miners earn by defending the network than by attacking it. It has more in common with a protection racket than a security firm.

MEV that happens on the network and in the native network token is healthy because it benefits defenders but not attackers. Attacks on the health of the network damage the value of that revenue, so it effectively only pays miners who are helpful. If Bitcoin miners start censoring Bitcoin transactions the price of bitcoin will go down and miners (who are paid in bitcoin) won’t earn as much. That keeps miners’ incentives aligned with the network.

MEV that happens outside the network or native token is quite dangerous however because any revenue that doesn’t depend on the health of the network is paid to both attackers and defenders. Ethereum miners, for example, can (and do) sell front-running as a service, letting sophisticated traders pay to cut in front of other transactions within a block. That probably reduces trust in DeFi and slows the growth of Ethereum as a whole, but miners still offer it and traders still pay for it because their incentives are not strictly aligned with the network.

At the moment Ethereum miners and the Ethereum network are, at best, frenemies. Developers are open about their intention to obsolete miners and switch the network to proof-of-stake in ETH 2.0. Miners are unapologetic about extracting revenue wherever they can, whether it serves the best interests of the network or not. But the entire network’s security rests on the premise that miners earn the most profit by serving the interests of the network, so that’s a precarious stand-off.

The miner incentives created by raw Ethereum transactions are mostly healthy but the incentives created by the DeFi economy are much more complicated and potentially adversarial. In some sense the native Ethereum economy is in a race against the DeFi economy — if the DeFi market overtakes the native market miners may find it more profitable to manipulate the network than to sustain it.

At time of writing Ethereum miners are earning ~$40M/day. That means at most Ethereum security can support ~$40M/day worth of DeFi MEV before the security model breaks down and miners make more money by exploiting the network than operating it. Uniswap alone is processing around ~$1.6B volume worth of trading/day. The growing DeFi economy is usually presented as an asset for Ethereum but I think the potential risks are under-appreciated.

In fairness, the majority of the tokens traded on Uniswap implicitly depend on the success of the Ethereum economy — they mostly create benign MEV because (like the native token) they would not survive a hostile attack on the network. USD-backed stable coins on the other hand keep their value outside the network, in someone’s bank account. That value might be inconvenienced by the need to evacuate Ethereum, but it wouldn’t be destroyed.

The value of USD-backed stablecoins surviving a network attack means USD-backed stablecoins can potentially bribe a miner to attack the network in a way that native tokens cannot. That’s what people likely mean when they talk about an on-chain USD flippening. If the size of the DeFi economy (as measured by on-chain USD) grows larger than the size of the Ethereum economy (as measured by the market cap of ETH) strange things may start to happen.

Lessons from the Death of Diem

We last spoke in December about Diem-née-Libra, Meta-née-Facebook’s attempt at building a stablecoin which formally ended this week with a firesale of its treasury to Silvergate Capital. Diem had access to the userbase, technical expertise and war chest of Metabookface but was unable to overcome opposition from (checks notes) literally everyone. Not wanting Facebook in charge of money is a bipartisan issue.

The problem of course wasn’t that Facebook couldn’t figure out how to build a stablecoin or couldn’t find a market for it — the problem was that they asked permission to launch it. Tether on the other hand launched their stablecoin without anyone’s permission and rose to an $80B market cap with 24 employees and a steady stream of legal troubles.

Fortune favoring the lawless is a consistent pattern in crypto. ICOs that ignored regulations outraised the ones that tried to adhere to them even accounting for the eventual fines. OHM forks have raised billions offering six-figure interest rates but Coinbase, BlockFi and Gemini have been blocked by the SEC from launching modest lending products. Regulators seem content to treat the compliant companies harshly and ignore the existence of anything non-compliant.

That might not be especially fair but it’s probably not entirely foolish. In a previous era regulator’s authority stretched to the horizon, but now there are some projects (most notably Bitcoin) that are definitely beyond their reach. It makes sense to me that regulators would try to defend their authority by asserting it especially fiercely over the areas they already know while they scramble to understand where new limits to their powers are appearing.

The flip side of that argument is that many of the lawless projects I just listed are still very much fringe by the standards of traditional finance. A currency used for payments on the Facebook network would not have been — arguably the death of Diem is a testament to the idea that government is entirely able to quash projects when they grow large enough that it bothers to notice them.

It is in that context that I find it interesting to interpret these comments by former Diem executive David Marcus:

Other things happening right now:

Presented without comment:

They now default to listings that expire in a month.

Some subtlety here: there is actually no listing on the blockchain itself, there is only the OpenSea contract and your proxy contract. The OpenSea contract will process any matching and signed pair of buy and sell orders, but the listings themselves are stored off-chain. That's why the exploit has been slowly dripping out instead of all at once and also why naively canceling the listing as OpenSea suggested was so dangerous. Canceling the listing reveals the secret transaction attackers need to match for the exploit to work.