The SEC is acting in bad faith

Plus ontology, teleology and a modest $35M mansion

In this issue:

The SEC is acting in bad faith

If it can’t be measured it can’t be bought (reader submitted)

Nothing too extravagant mind you

Thoughtful analysis from a bearded frog

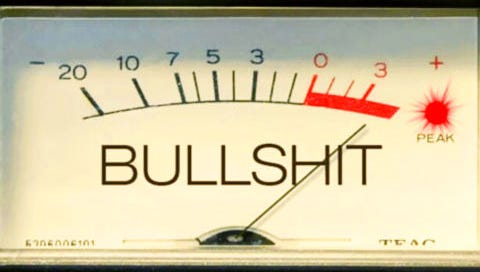

The SEC is acting in bad faith

Back in April, CryptoTwitter personality @cobie tweeted about finding an ETH address that spent hundreds of thousands of USD exclusively buying tokens that Coinbase announced were "under consideration for listing" the next day.

When a token is listed on Coinbase for the first time it often experiences a bump in price thanks to new liquidity and exposure to new demand. That means anyone with advance knowledge that a token would be listed (or announced as a candidate for listing) could buy that token before it was listed and then sell into the price spike afterwards, profiting on the basis of their knowledge of the upcoming listing. In a stock market that would be obviously illegal but in crypto the convention is often to just assume no laws apply.

Coinbase insiders have been taking advantage of their position for a long time — since at least the listing of Bitcoin Cash in 2017. cobie himself had been ranting about frontrunning problems in new Coinbase listings for months. So cobie’s tweet caused some conversation but it didn’t necessarily stand out — I wrote about it briefly at the time in the "Other things happening now" section.

One person it did probably stand out for was Ishan Wahi, a Product Manager at Coinbase at the time. He and his brother Nikhil Wahi and friend Sameer Rahani were responsible for the ~$1.5M worth of illicit trades cobie had tweeted about. Coinbase started an investigation on the basis of this tweet that eventually culminated in Ishan attempting to flee the country before being detained by law enforcement. It turns out that according to the SEC and the FBI laws do in fact still apply. The three men were charged with wire fraud and insider trading.1

Coinbase was predictably quick to take a victory lap:

This is, of course, complete garbage. Coinbase’s internal protections against abuse were so weak that the first people to notice were random Twitter accounts. Wahi and his cohorts were able to trade ~$1.5M in thin markets without causing any scrutiny. Coinbase was absolutely derelict in their duty to protect their users from this kind of employee abuse. The fact that cobie busted their chops enough to eventually do the bare minimum does not redeem them.

Coinbase probably isn’t thrilled about the outcome either, though. Starting on page 23 of the 62 page insider trading complaint the SEC lays out the case that nine tokens specifically (AMP, DDX, DFX, KROM, LCX, POWR, RGT, RLY, XYO) should be considered unregistered securities. This is isn’t the first time the SEC has argued that certain tokens should be considered securities but it is the first time that it has made that argument in a case that didn’t involve the creators of the token or the exchanges the token is sold on.

The most obvious explanation for this approach is that the SEC is seeking to establish precedent for cryptocurrencies as securities in a backdoor way that makes it harder for those projects or exchanges to defend themselves. News broke later that week that the SEC is investigating Coinbase for its role in having listed tokens the SEC claims are unregistered securities. Shares of COIN 0.00%↑2 dropped a little over ~20%.

It’s hard to see that as anything other than deliberately punitive. As Coinbase’s Chief Legal Officer Paul Grewal points out, Coinbase actually worked with the SEC on their regulatory review process. You can disagree with where Coinbase decided to draw the line on particular tokens but they are obviously eager to adhere to the regulatory guidance wherever it exists. If they are not in compliance the fault is clearly with the SEC for not having made the rules more clear.

Even other government officials seem to view the SEC’s tactics as a regulatory land grab — CFTC commissioner Caroline Pham called it "a striking example of regulation by enforcement." The SEC doesn’t seem to be worried about protecting investors but instead about extending it’s authority and influence. It’s the same pattern of attack that led them to hold GBTC investors hostage or let the Terra/Luna and Celsius ponzis explode while bickering with BlockFi and Coinbase over interest rates on lending products.

The SEC is derelict in their duty and investors are paying the price.

If it can’t be measured it can’t be bought

"About your post on ESG investing: normally I'm very much in the "perfect is the enemy of good" camp, so my intuitive response to the article was "but doesn't this incentivise at least some behaviours we care about (e.g. more clean energy)?" – but in practice I'm having a hard time finding any hard data to either support or refute it @knifefight did you come across anything in your research that points to ESG having specific, measurable impacts (useful or not) that would suggest how ESG might be done right? Or do you think it's a failed experiment entirely?" — JN

My main objection to Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) investing is almost exactly that it can’t be measured. It is possible to measure profit because it is about what happened — it compares the past to the present. You can’t measure moral impact because it is about what would have happened if you hadn’t invested — it compares the present to an unknowable alternate timeline. The profit equivalent would be trying to measure how much money you could have made.

Unfortunately I don’t think ESG investing is redeemable. Even if we could all agree on a system for sorting "good" companies from "bad" companies it’s not clear to me that a strategy of only owning "good" companies is even morally desirable. The end result of that strategy is all the morally challenging businesses being sold to all the morally dubious investors at a discount. Maybe the morally superior approach is to invest in all the "bad" companies and use your influence to make them better?

There is a lot of data in ESG investing — in some sense that data is what ESG investors are paying ESG funds for. But the data those funds produce is all about how they choose their investments, not about what effect investing that way actually had.3 That’s a bit like asking a child about their grade on the test and them answering by telling you how hard they worked. Be suspicious.

Other things happening right now:

Disgraced founders of Three Arrows Capital (3AC) Kyle Davies and Zhu Su gave an astonishingly tone deaf interview with Bloomberg from an undisclosed location. In the interview they describe the collapse of 3AC as "regrettable" and object to the idea that they lived an extravagant lifestyle. Su for example pointed out that his family “only has two homes in Singapore.” He is currently selling one of those two homes (the spare one?) for $35M, which sounds pretty extravagant to me, but maybe things look smaller from the deck of a yacht?

When a decentralized network becomes useful it inevitably becomes congested and expensive to use. Decentralization is always expensive. But new L1 networks that haven’t become crowded yet always appear cheap. They can also freely adopt any tech developed by existing networks and redirect their R&D budget towards marketing their apparent advantages. The result is a never ending cycle of new L1s that rotate in and out of fashion. Here is an interesting essay exploring this dynamic by ChainLinkGod, who is quite a bit more insightful than their name and pepewizard avatar would make you think.

Presented without comment:

If this sounds familiar you may be thinking of Nate Chastain, formerly head of Product at OpenSea, who was recently charged by the SEC for doing pretty much exactly this only with NFTs being promoted by OpenSea. So probably don’t do crimes with tokens whether they are fungible or not. (Not legal advice)

The ticker is a new substack feature. The % change is pegged to the 24hr mark, which is a bit confusing next to the 20% in the sentence, but it’s also meant to cross-link with other creators writing about the same ticker so I am hoping it helps a few new people find their way Something Interesting. We’ll see!

Interestingly if you are an ontological ESG investor (e.g. a vegetarian who does not want to own meat companies) as opposed to a teleological ESG investor (e.g. someone who is hoping to mitigate the effects of climate change) that data could actually be sufficient. My sense is the vast majority of ESG funds and investors are teleological — advertised and selected for their ability to actually impact the world. But if your main goal is just to own a certain class of company because you feel it better reflects your values (and not because you think your decisions actually shape the market) then a lot of my objections actually fall apart. You can invest in anything you want if you find it beautiful. 🙂