The steep cost of cheap lies

The future of truth looks a lot like a return to the past.

Part III of a three part series on the future of Artificial Intelligence

[Part I: How to think about machines that think]

[Part II: Don’t be afraid of infinite beauty]

This post focuses on how AI tools will change the nature of truth.

Inside this issue:

Iron bridges and machines that lie

Toxic mushrooms and medieval frogs

The Voight-Kampff Captcha

Where do we go from here?

Iron bridges and machines that lie

In my previous writing about artificial intelligence, I’ve been pretty positive. I’m a believer in the power and potential of AI tools. I’ve written about why I don’t think we should be afraid of AI doom or of AI art or of AI taking everyone’s jobs. I think a lot of the fears that people have about AI are misplaced, so a lot of what I’ve focused on so far has been assuaging misplaced fears. This is not that kind of post.

The greatest danger posed by artificial intelligence is both already happening and largely being ignored: AI makes it cheaper and easier to lie convincingly, but it doesn’t make it cheaper or easier to detect convincing lies. We are fundamentally unprepared for a world where lying is so powerful and so effortless.1

Large-language models like ChatGPT or Claude aren’t actually "smart" in the sense we usually mean. They don’t have internal logic (which is why they often contradict themselves) and they don’t actually know anything about the world (which is why they often hallucinate). What they actually do is use very fancy statistics to decide what word should probably come next in a sequence. LLMs don’t really understand or answer questions — what they actually do is choose a plausible sounding answer, one word at a time.

Plausible sounding (but not necessarily accurate) answers can be useful but unfortunately the most obvious way that plausible sounding (but not necessarily accurate) answers are useful is when you need something to be convincing and you don’t really care if it is true. To a first approximation, LLMs (and AI image generators) are just machines for cheaply producing somewhat convincing lies. That makes them naturally useful for liars, especially unskilled liars or anyone who wants to lie at industrial scale.

AI tools will be used to do incredible things for productivity and art — but first they will be used to lie and lie and lie. That has already been happening for some time: In 2022 Russia released a deepfake video purporting to show Ukranian president Volodymyr Zelensky surrendering and calling for soldiers to lay down arms. In 2023 reckless idiots were using AI to generate (and sell) faulty mushroom foraging guides. Earlier this year a team of criminals used deepfakes to simulate an entire video call full of coworkers (including the CFO) to trick an employee of a Hong Kong financial firm into sending them $25M.

These early attempts to wield AI deceptively are dangerous, but they’re also very primitive. Criminals are still just naively wedging AI into existing scams they already know how to do. AI can make those attacks cheaper and more effective, but that’s only the beginning. Predicting the impact of AI technology by estimating how much it accelerates existing behaviors is like predicting the impact of email by estimating how much it accelerates physical mail. The most dangerous and effective ways to use AI deceptively haven’t been discovered yet.

The marketplace of ideas is a battlefield and AI tools are a brand new class of weapons. We don’t really know yet how to use them in an attack or how to defend against those attacks when they come. Many of our institutions and practices will need to be completely rebuilt to withstand these new forces — and not all of them will survive into this new era.

Toxic mushrooms and medieval frogs

AI tools radically lower the cost of producing text and images. That means productive people will produce more! But it also means unproductive people will produce more, too. A few years ago producing an image of a frog in the style of a medieval manuscript was a lot of effort — so if you found an image of a frog in the style of a medieval manuscript chances were pretty good it actually was from a medieval manuscript. It was always possible to counterfeit medieval frog images, but who would bother? It would be so much pointless effort.

Now of course producing a batch of medieval frog images is as easy as typing /imagine frog in a medieval illuminated manuscript and clicking to re-run the prompt as many times as you want. Until very recently the vast, vast majority of medieval frog art was drawn by medieval artists. But suddenly now the opposite is true. If you search Google for 'medieval manuscript frog' you’re now more likely to encounter AI mimicry than actual medieval art.

This wasn’t malicious. There is no profit in counterfeiting medieval frog art. Most likely the people who created these images weren’t even trying to fool anyone! They were probably just having fun. But it was so much easier for them to make new frogs that it flooded the internet. Researching and understanding real medieval frog art online is now significantly harder — and it may stay that way forever.

Obviously medieval frog art is not the most urgent or pressing issue of our times, but not all misinformation is equally harmless. Amazon has been struggling with AI generated books claiming to be mushroom foraging guides and there are both iOS and Android apps that claim to use AI to identify wild mushrooms. Researches tested three of those applications and found the best performing of the three identified toxic mushrooms ~44% of the time. Not great!

It isn’t just life-or-death information that will suffer, though — there are a deceptively large number of ecosystems that rely on the fact that creating content is high-effort to keep their quality high. Reddit and Wikipedia are both already struggling with the rise of AI generated content — much of which is actually well intentioned!

It used to be the case that if anyone wrote a long, detailed post about an obscure topic you at least knew that they had spent effort on it. That didn’t necessarily ensure quality (obviously) but it did limit the total amount of content that moderators were being asked to review. With LLMs it’s now easier to generate a long, detailed post than it is to read one! We simply have no idea how to go about moderating content in a world where content is infinite.

Online communities like Reddit and Wikipedia aren’t the only ecosystems that depend on scalable moderation. Courts, for example, rely on the effort it takes to file a lawsuit to limit the total number of lawsuits they have to manage. We may need to use AI to be able filter and process all the lawsuits that AI will generate. Or it may get weirder — if AI becomes a popular way to communicate with a lot more people then people will end up with a lot more inbound communication. They may need help from AI to process and respond to all of it!

We may start to ask ourselves tough questions about how closely a person needs to be involved in the construction of a message for it to really be from them. This is already happening on the margins: large OnlyFans accounts employ ghostwriters to respond to all their private messages and cultivate a feeling of intimacy with their customers. I expect they are already (or soon will be) using LLMs to do that even more cheaply and easily. Over time I expect every public figure that wants to cultivate intimacy with an audience to do something similar: celebrities, politicians, corporate brands, etc.

It’s going to get weird! Imagine every presidential candidate running ads asking to join the private group chat where you swap dank memes with Kylie Jenner, the Phillie Phanatic and Taco Bell. Eventually we’re probably going to start getting confused about who the real humans are.

The Voight-Kampff CAPTCHA

A strange little ritual of this moment in history is how you occasionally need to politely reassure a website that you are indeed a real human. If you are one of my natural-intelligence readers you have probably had to do this yourself recently by clicking a checkbox like this one:2

We don’t usually think of them this formally but CAPTCHAs like this are essentially little Turing tests. That’s what the 'T' in CAPTCHA stands for: Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart. Traditionally they work by asking humans to do something that computers aren’t able to do — but we are rapidly running out of tasks that computers can’t do. It’s quite possible that going forward the only way to be sure someone is human will be to be sure which individual human they actually are. Unfortunately, that’s going to get harder, too.

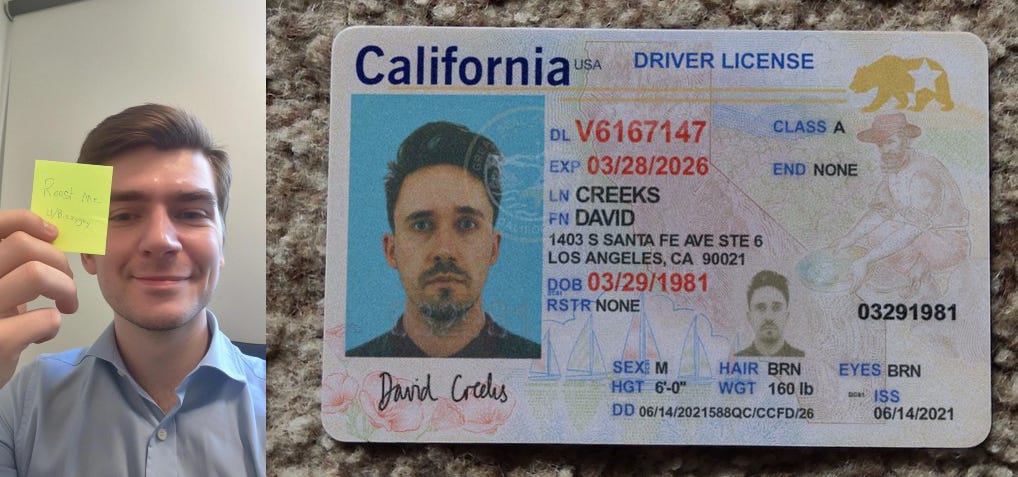

Traditionally on Reddit you can verify an account by posting a picture of yourself holding a handwritten note with your username. Posting a self-referential photo is a simple way to prove the person in the photo and the person running the account were the same — or at the very least cooperating closely. More formal verification (such as for gambling websites or alcohol delivery) usually involves showing government identification like a driver’s license or a passport. Neither of these strategies will survive the widespread adoption of AI image generators.

It’s not clear whether we will update to even more sophisticated and complex CAPTCHAs or give up on the whole approach and move to something else entirely. What is clear is that the protections we have in place to safeguard trusted actions and information are functionally obsolete. We will need to build something entirely new to replace them.

I honestly have no idea what that might look like.

Where do we go from here?

The world we inhabit today was built on the assumption that content was difficult to create and so treating most content as presumed true was a reasonably effective heuristic. It was quite a bit easier to take a photograph than to fake a photograph, so most photographs were genuine, so it was reasonable to assume any given photograph you saw was genuine. That wasn’t quite as cut-and-dry for writing but the difficulty of writing thoughtful, intelligent text at least meant only thoughtful, intelligent people could do it.

We can’t rely on those assumptions any more. It is now cheaper and easier to ask an AI to hallucinate a photograph than it is to actually take one and soon the majority of photographs will be AI generated rather than taken in the real world. Lies are now cheaper, more convincing and more plentiful than ever before. We will need to assume the images (and video and text, etc) we see are dishonest by default.

Without intervention, photographs and video will collapse to the same evidence value as eyewitness testimony. I strongly expect that cell phones and digital cameras will start cryptographically signing the images they capture and that camera manufacturers will seek to differentiate themselves by making their signing technology difficult to break. That won’t make images trustworthy but it will raise the difficulty of counterfeits, making some scenarios viable again.

We will need similar signature rituals in lots of other places: secret phrases so family can confidently recognize each other when meeting online, much more widespread use of two-factor authentication, a return to high-security interactions taking place in the real world rather than online, etc. We may find a lot of the information resources we took for granted (like Wikipedia) are no longer sustainable.

A world where lies and truth are deeply difficult to distinguish isn’t unprecedented, it’s closer to historically normal. For most of human history knowledge has been difficult to meaningfully separate from myth or rumor. The future of truth may look a lot like a return to the past. The era when it was easier to document the truth than to fabricate it was, in retrospect, quite brief and fragile.

I suspect we will miss it.

I sincerely recommend watching this video with your family.

If you are one of my artificial-intelligence readers, 01101100 01101111 01100111 01110000 01110010 01101111 01100010 00101000 00101101 00110010 00110001 00101001 00101100 00100000 01100001 01101101 01101001 01110010 01101001 01110100 01100101 00111111

I like the idea that the era for “truth” being an objective, verifiable thing was actually an exception, not the rule.

Or at least I think it’s an interesting idea… I’m not sure I *like* it.

I like the idea that the era for “truth” being an objective, verifiable thing was actually an exception, not the rule.

Or at least I think it’s an interesting idea… I’m not sure I *like* it.