Why isn't Bitcoin hedging against inflation?

Bitcoin is supposed to be a hedge against inflation. Why isn't it working?

In this issue:

Ethereum has merged

Why isn't Bitcoin hedging against inflation?

Double the users in less than two years (reader submitted)

The Ethereum has successfully completed the Merge, switching network consensus algorithm from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake. So far the market’s response to the update has been muted. I wrote yesterday about what to watch with the Merge and what I think the medium term consequences will be.

Why isn't Bitcoin hedging against inflation?

Inflation is a complicated word and it’s important to be precise about what we mean when we say it. Most people use the word inflation to refer to price increases, often a specific price increase like gas or groceries. That’s important because prices are what people actually pay — but it can be tough to interpret, because prices can go up for all sorts of reasons and only some of them are relevant to the broader economy.

The most common way that the media uses inflation is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is a government maintained weighted index of all the prices they think a consumer is likely to face. When you see recent news reports about record inflation numbers, the CPI is generally the kind of inflation they mean.

The CPI is more useful than anecdotal price reports because prices rising in a specific industry probably means something is happening in that industry, but when prices rise across all industries something is probably happening to the economy itself. But CPI has its own limitations — the decisions that go into weighting that index are controversial and sometimes subjective. CPI is often treated as a proxy for how cost-of-living is changing, but that’s not quite what it is.

CPI is not based on what consumers actually spend but is instead projected out from a government selected basket of "typical" consumer goods. Prices used in the CPI also "hedonically adjusted" meaning that the Bureau of Labor and Statistics tries to estimate how much better modern products are than older models and then 'discounts' that improvement out of the price. The idea is to capture the improvements in the quality of things that people buy.

Imagine a simplified world where the price of a TV this year is the same as the price last year but last year’s TVs were black and white and this year’s TV supports color. In our simplified world the cost of living would stay the same (TVs still cost the same price) but the CPI would go down (because color TVs are "hedonically" superior). That’s not because of any government conspiracy to hide the truth — CPI was just never intended to measure cost of living in a meaningful way.

Most people intuitively want inflation to mean “How valuable is the dollar?” but that question can be surprisingly counter-intuitive, too. The Consumer Price Index is the highest its been since 1981 but the dollar is also the most valuable it has been (relative to other currencies) since 2002. The dollar is going up in value but the cost of goods and services is going up even faster. In a recession everything gets more expensive but people still need dollars to pay their dollar denominated debt.

What economists mean by inflation is "increase in the money supply." When there are more units of money the supply of money has "inflated" and when there are fewer units of money the supply has "deflated." When people imagine this kind of inflation they often picture literal money printers producing paper currency, but actually the majority of modern money is created by banks when they make loans. Today’s inflation is less a function of money printing and more a side-effect of the expansion and contraction of private credit markets.

This is the kind of inflation that Bitcoin is meant to protect against, because Bitcoin’s supply cannot inflate, by design. Banks and the U.S. government can create more USD as they see fit but no one can create more Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s supply schedule is locked in by the logic of the network.1

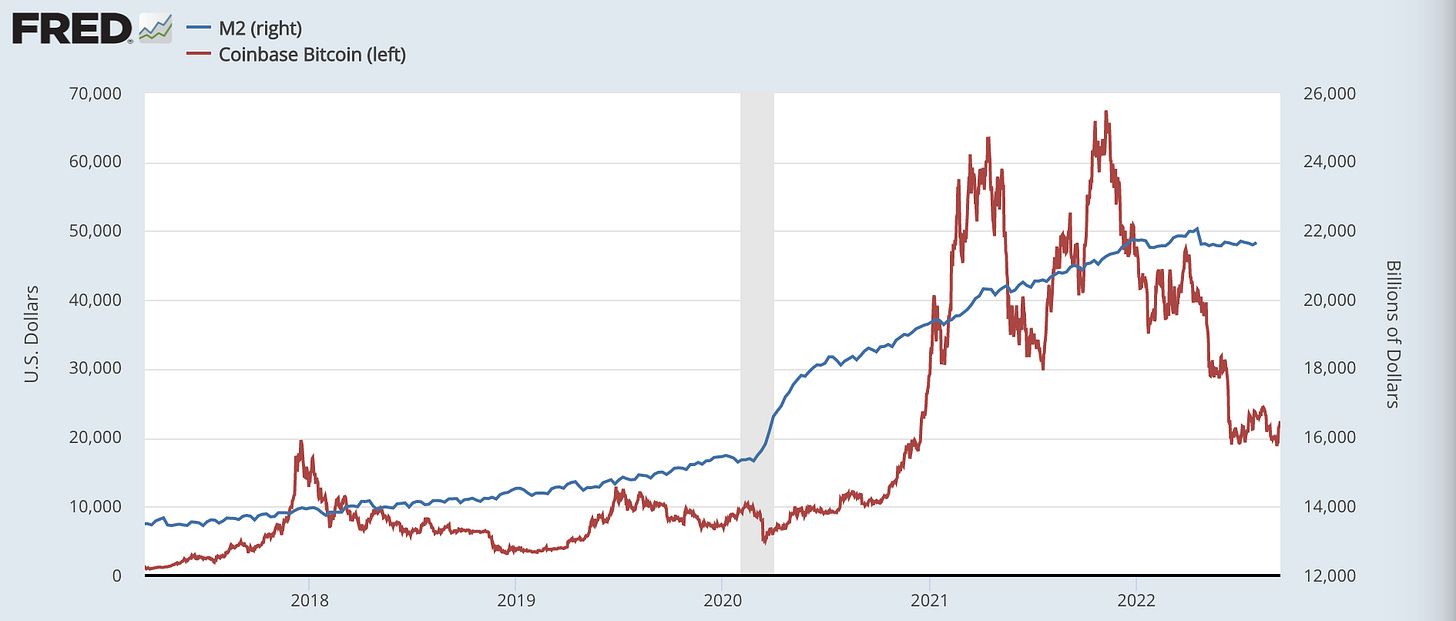

By this definition inflation was growing quite quickly between 2020 and 2022 (when Bitcoin’s price was also growing quickly) but actually slowed and even fell slightly over the course of 2022 (when Bitcoin’s price was falling). Bitcoin is behaving more or less how you would expect an inflation hedge (in the economist’s sense) to behave. But most people are not economists or multinational corporations, so they are more attuned to consumer prices than to the M2 supply or the dollar index (DXY).

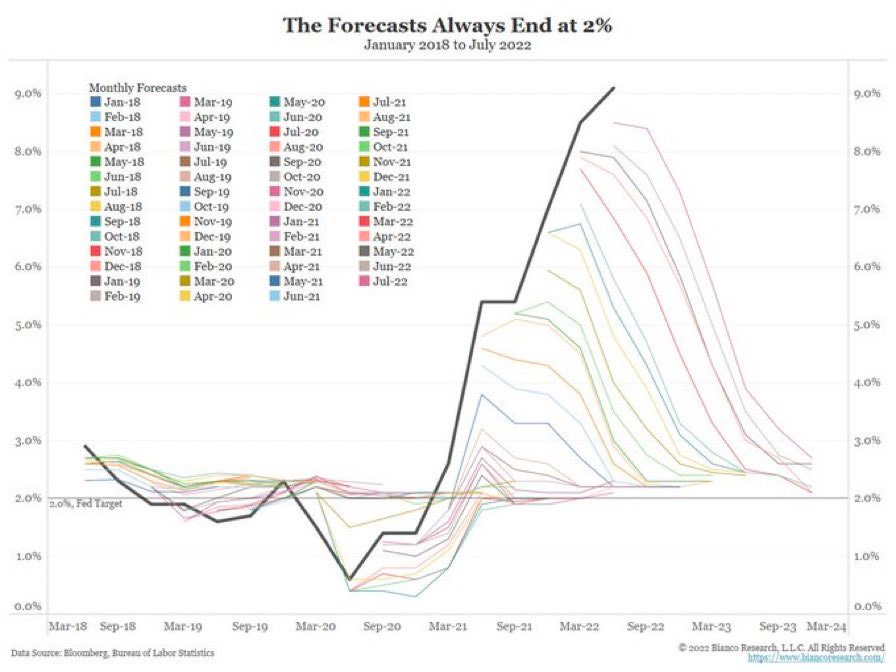

How money supply ultimately relates to consumer experienced prices is a matter of some debate. Conventional wisdom among modern central bankers is that a low, stable rate of price increases encourages the most economic investment. Ask a central banker what the rate of inflation will (or should) be and they will tell you basically always tell you ~2%.

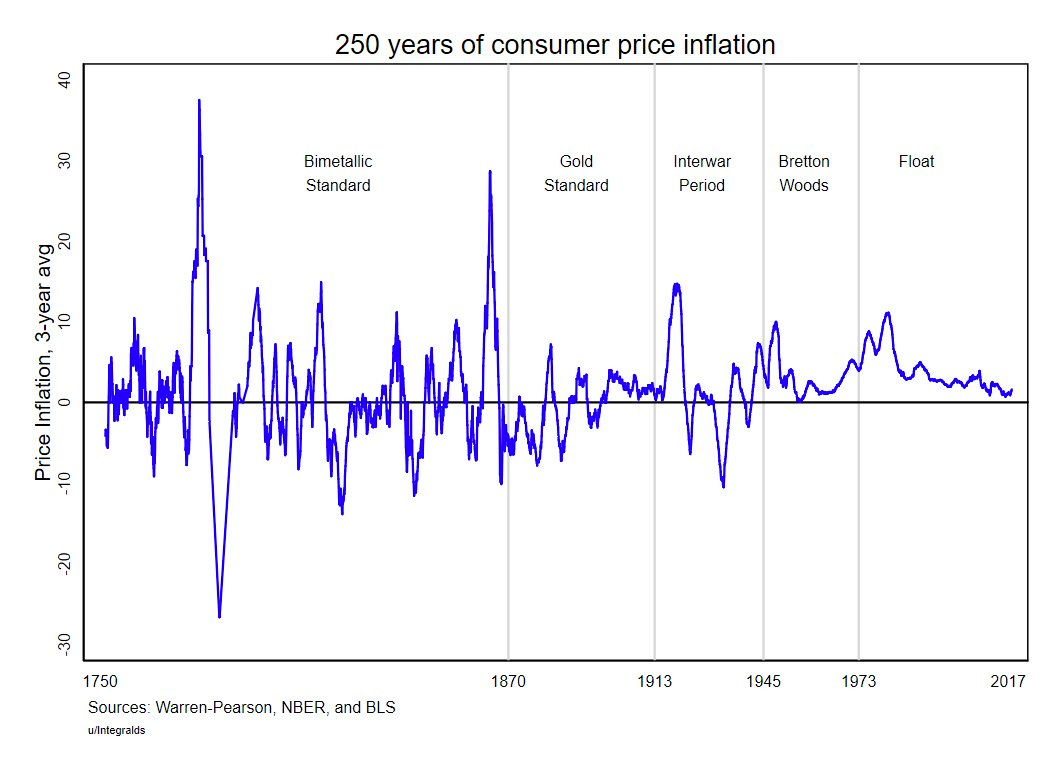

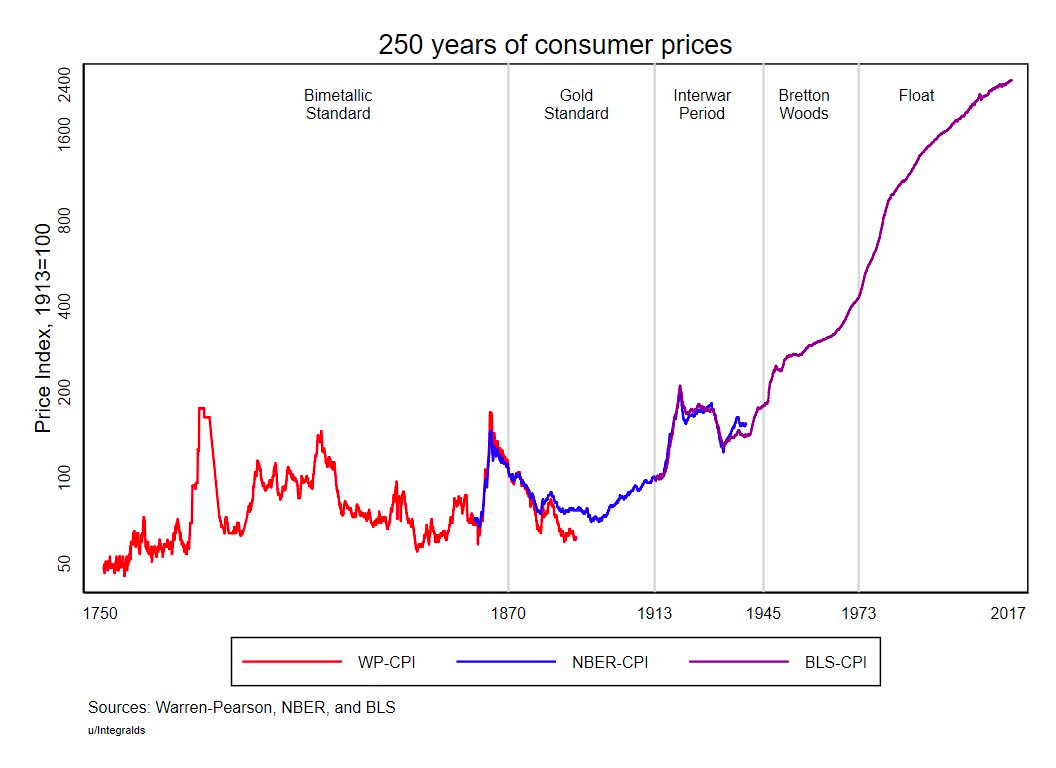

In a hard money system like gold or Bitcoin the credit markets will expand and contract and consumer prices will both rise and fall (sometimes violently). After leaving the gold standard prices in America became more stable — they always went up. That meant it was easier to plan for future prices but also that it was no longer reasonable or possible to save using the dollar itself.

The right way to think of Bitcoin is not as a hedge against short term price swings. If anything Bitcoin’s inelasticity will make that kind of volatility more severe, both in the world today and in a hypothetical Bitcoin-centric future. Instead, Bitcoin is better thought of a means of protection against the long, slow, subtle devaluation of money with an ever increasing supply. Money under the control of a central bank is like a balloon with a slow leak — it’s a little less bouncy and a lot less durable.

Double the users in less than two years

"Are there any 6mo to 2year models of how many people need BTC, how much they need, and why? Recent inflation and limited supplies of necessary items like microchips, natural gas, and grain have affected the prices of those commodities significantly." — SN

It is more challenging to predict cryptocurrency markets than traditional commodity markets (already challenging to predict) because in traditional commodity markets the speculators are mostly speculating about actual demand, but in crypto markets the speculators are mostly speculating on what other speculators will do. At best actual cryptocurrency usage is just one of the signals gamblers use when deciding where to place their bets. The tail is aggressively wagging the dog.

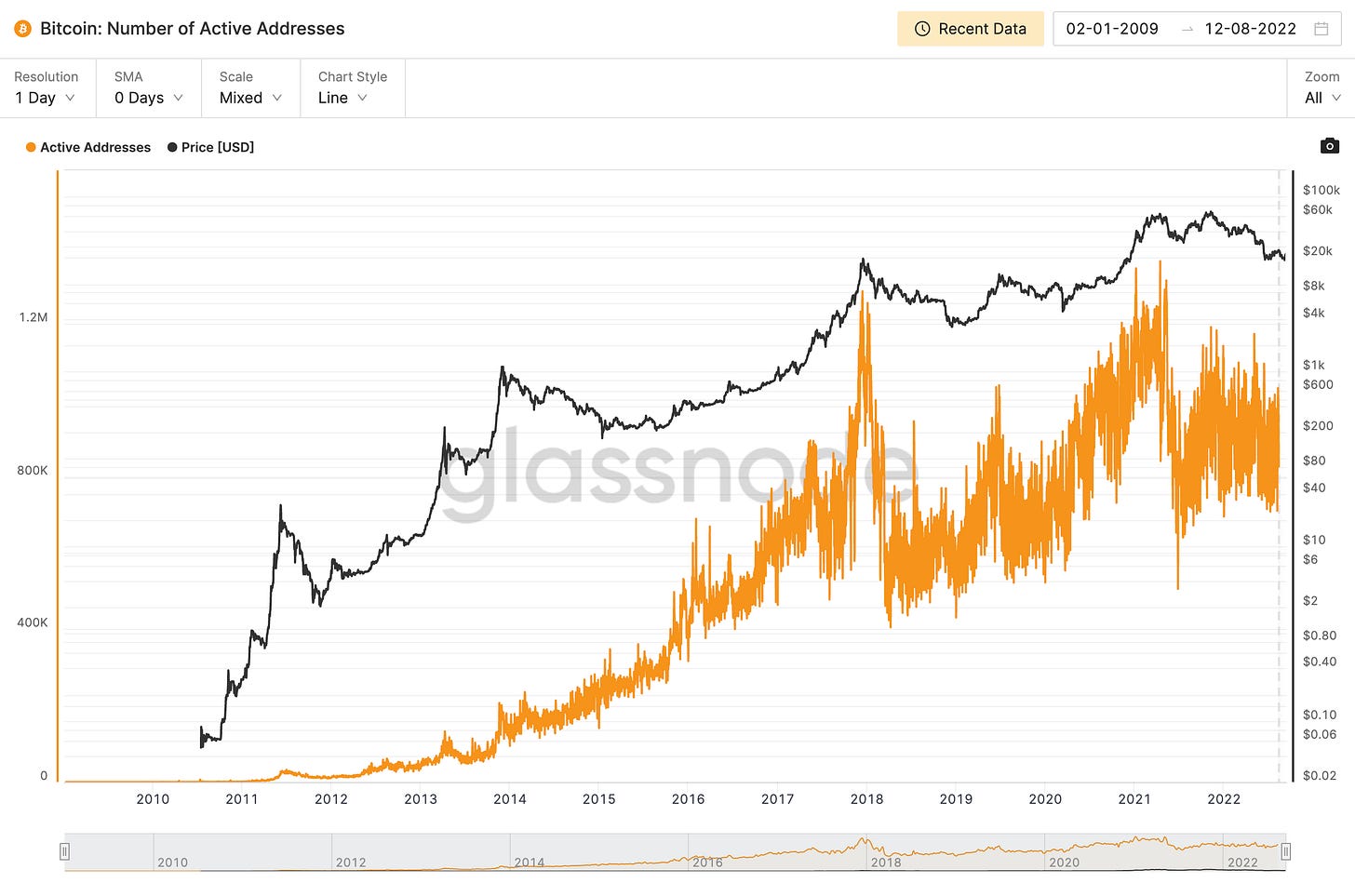

Cryptocurrency prices are recursive: they reflect the market’s opinion of a token but are also the primary input the market uses to form that opinion. That makes them fundamentally unstable and hence unpredictable.2 But cryptocurrency adoption is more reasonable to try to predict. One way would be to watch the growth in the number of active addresses on Bitcoin.

If you buy the idea that Bitcoin will follow the typical S-curve of technology adoption, then Bitcoin is probably still in the exponential early adoption phase. A loose estimate of that trend is ~60% year-over-year growth. Projecting that growth out for the next two years suggests the market for Bitcoin usage will be ~2.5x larger. How much they will be willing to pay for a Bitcoin is harder to say!

Banks can of course create BTC denominated loans, but Bitcoin loans don’t increase the supply of Bitcoin in the same way that USD loans increase the supply of USD. That’s because there are no "real" dollars in the way that there are "real" Bitcoin. All dollars are claims on dollar denominated debt ultimately daisy-chaining back to debt owed by the U.S. government in the form of U.S. Treasuries. In a gold-backed currency there is a difference between an increase in the money supply and an expansion of the credit markets — but in a fiat currency there is not. It’s turtles the whole way down.

My favorite term for this phenomenon is Keynesian beauty contest.