Who holds the power in NFTs?

Commercial rights, marketplace royalties and using Kevin Rose's Moonbird to fight back against the Panda menace

In this issue:

What gives you the right? (reader submitted)

Royalties are doomed (but not artists)

Reddit doesn’t want to say NFT

What gives you the right?

"What's the Something Interesting view on the cc0 movement?" — ANI

The Moonbirds are a collection of 10,000 pixelated owl avatars released by Kevin Rose (formerly of Digg.com). They initially sold back in April for ~2.5 ETH (~$7600 at the time) and quickly skyrocketed up to ~38.7 ETH (~$113k at the time) a week later. At time of writing Moonbirds are trading for ~14.5 ETH (~$22k). That might seem like a lot for a pixelated owl picture but keep in mind these tokens also gave their holders stickers and a free fanny pack, so they’re honestly delivering more utility than most NFT collections at this point.

As desirable as a custom fanny pack is, it was also a surprise announcement so it probably wasn’t the main reason people were paying six figures for Moonbirds back in April. Perhaps at least some of the buyers were thinking of this section of the FAQ on the Moonbirds launch website at the time:

Giving NFT holders the commercial rights to the arts they held the token for was an approach pioneered by the Bored Ape Yacht Club and is widely considered one of the key elements of their success. There are Bored Apes who are now the brand identities of coffee, wine, beer, hot sauces and countless strains of marijuana. The Arizona Iced Tea company owns an ape and so does Adidas. There is a four-ape band signed by Universal Music Group that has a co-marketing campaign with M&Ms. It is not yet clear how sustainable any of it is, but there is a surprisingly thriving ecosystem of people using their apes to build brand identities and sell sponsorships.

At the beginning of August however Rose and the Moonbirds team decided to go a different direction and released the commercial rights to Moonbirds via a creative commons license known as CC0 or no rights reserved. In effect rather than giving the commercial rights to the Moonbirds images to the holder of that particular NFT they were giving all the rights to all the Moonbirds to everyone. The holders were getting commercial rights but not commercial exclusivity.1

Promising rights to holders but giving them away instead was (perhaps not surprisingly) controversial with the holders. Moonbirds are not the first NFT collection to release under a CC0 license but they are the most expensive and the announcement came after months of trading without any consultation or warning to the community. Many holders felt deceived.

Moonbirds are not the first NFT collection to release their rights under a CC0 license but they are probably the most expensive. CC0 licensing is often appealing to smaller collections that don’t expect to have enough attention to charge businesses a fee to use their art — instead they give the commercial rights away as a form of advertising. The hope is that anyone using the art to do something interesting is increasing its cultural importance and raising the value of the NFT even if the owner can’t charge rent to the people using the image.

Objecting to CC0 isn’t just about the money, though. CC0 also means there is no grounds for an owner to object to their Moonbird being used by a political campaign they oppose or in a vulgar Rule 34 parody or being adopted as a symbol by a hate group the way white nationalists co-opted Matt Furie’s Pepe the Frog. I can sell a hot sauce with Kevin Rose’s profile picture on the label and dedicate all the profits to neutering wild pandas and he can’t stop me. That’s the power of CC0!

To be blunt I think the obvious explanation for Rose’s and the team’s decision to abruptly shift the licensing model is that they were working on some kind of lucrative business opportunity for the team and giving holders rights to their individual images was making that deal more complicated in some way. The CC0 model makes it harder for individual Moonbirds holders to license their individual Moonbirds but it probably makes it easier for Rose to license the collection out as a whole.

The controversy was enough to cause Galaxy Digital to do a thoughtful survey of the licensing arrangements of various NFT projects as they stand today and the results are not flattering:

The vast majority of NFTs convey zero intellectual property ownership of their underlying content (artwork, media, etc.)

Many issuers, including the largest Yuga Labs, appear to have misled NFT purchasers as to the intellectual property rights for the content they sell.2

In general the licensing agreements for the major NFT projects are legally malformed and probably don’t convey anything close to the rights the projects marketing materials imply. It would be easy to assume (as many are) that this means NFTs as a means of transacting in IP rights are dead but I don’t think that’s true. It seems more likely to me that Yuga Labs will use its resources to refine and perfect the legal structure that governs its approach than that it will suddenly reverse approaches. But even if it does another project will keep experimenting.

NFT projects today have malformed licensing. But that doesn’t mean that proper licensing is impossible. Now that we know how profitable such an arrangement can be the lawyers will eventually figure out a way to write it down.

Royalties are doomed (but not artists)

Most NFT collections today specify royalty rates — a percentage fee charged to future secondary buyers based on the price they paid. Royalty revenues can be quite significant: Yuga Labs has earned over ~$150M in secondary royalties so far. But although royalties are often hailed as a key feature of NFTs they aren’t actually enforced by the contracts themselves. Instead it is the marketplaces like OpenSea that actually enforce and collect the royalties that are requested by artists.

The rising competition between NFT marketplaces is driving down fees and the easiest prices to cut are the ones you are charging for someone else. So an increasing number of upstart marketplaces are choosing not to collect royalties on secondary sales and are instead treating it as a suggested tip the buyer can decide whether to indulge or ignore. That’s raised a lot of hackles among NFT artists and collectors about what the role of royalties is or should be in the space.

There aren’t any great ways to perfectly enforce royalties. You can do clever things to make it easier to use approved marketplaces or harder to use blocked ones, but it only introduces friction it doesn’t prevent anything. Even if you could force users to only sell inside an approved marketplace you couldn’t prevent them from transferring the bulk of the real price through an outside escrow service and trading on the royalty enforcing platform for only a nominal fee.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the natural price point for royalty rates is zero. NFT buyers and sellers will gravitate to the markets that have the royalty enforcement policy they prefer. If enough of them prefer royalty enforcement they will create a network effect that will drag more cost-sensitive buyers along with them. But marketplaces ultimately serve traders, not artists. If traders decide they would prefer that royalties be optional marketplaces will stop enforcing them.

That’s probably fine? For one thing, it probably doesn’t even make sense to lock in the same flat royalty rate forever and it definitely doesn’t make sense to do that for a finite list of approved marketplaces. Stuff changes.

For another, there are other perfectly reasonable ways to harness ongoing value from a project without needing to charge secondary royalties. The Nouns project for example produces and auctions one new NFT a day on the open market, effectively capturing a share of the current demand for Nouns directly instead of through fees.

Percentage fee royalties are primitive tools. Needing to evolve past them does not mean artists in the space are doomed.

Other things happening right now:

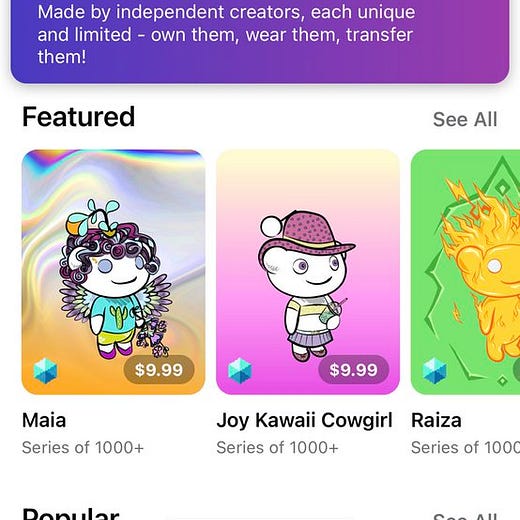

Reddit quietly launched a collection of Polygon NFTs that look about like what you would expect a corporate art collection to look like. Interestingly rather than calling them NFTs they are choosing to call them collectible avatars. I predict this feature will be as transformative and impactful as MOONs, the cryptocurrency they launched back in 2020. (Disclaimer: I used to work at Reddit back in 2019, before these features existed. It was a simpler time.)

NFT skeptics like to accuse NFT enthusiasts of money laundering and wash trading, but according to Blockchain analytics company Elliptic ~0.02% of all NFT transactions were associated with illicit activity. That makes obvious sense when you consider it. The point of money laundering is to make suspicious money look unobtrusive and normal. Piping money through the NFT market has the complete opposite effect.

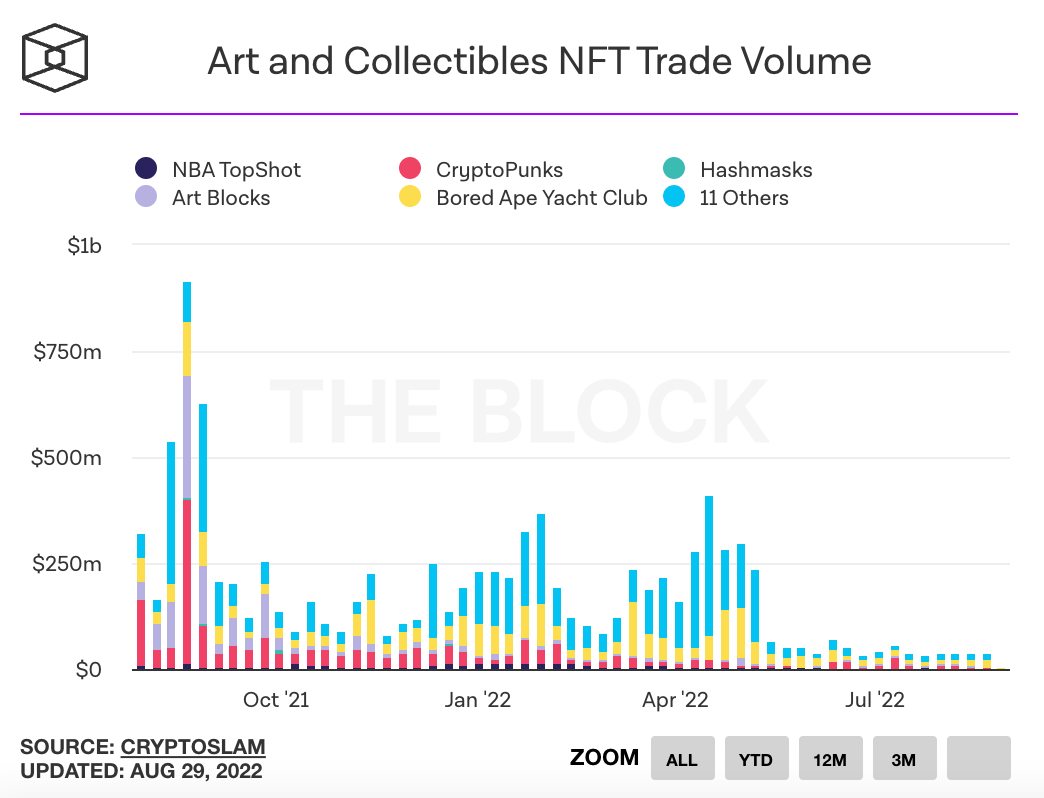

Trade volume across major NFT collections remains anemic:

Presented without comment:

The fanny packs remain exclusive to holders.

Periodic disclaimer: I hold several Yuga Labs NFTs.