The unexpected value of wasted space

If Bitcoin actually works as intended, there is no wrong way to use it.

Check out my recent op-ed in Bitcoin Magazine: Free as in Freedom is not Free as in Beer

The unexpected value of wasted space

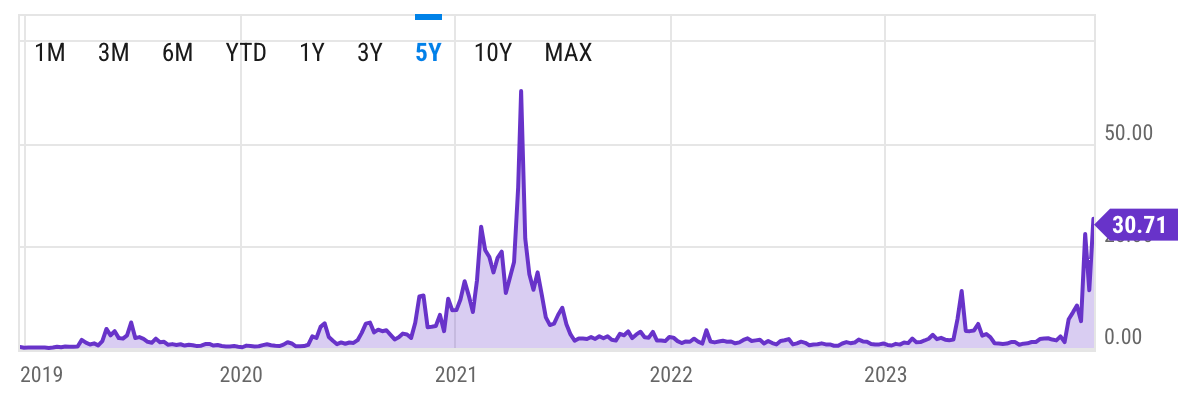

The price of Bitcoin is up ~160% over the last year, but transaction fees on Bitcoin have risen even more sharply. As of writing, average Bitcoin fees are almost $30/tx, the highest they’ve been since the peak of the bull market in 2021.

Fees are so high that block #821,485 paid 7.315 btc in transaction fees, more than (and on top of) the 6.15 btc block reward. This isn’t the first time fees have ever risen above the block reward but it has been pretty rare so far and building a healthy market for transaction fees is critical to the long term health of the network. I personally consider finding enough demand for transaction fees to be Bitcoin’s most existential long term challenge, so the arrival of new demand for Bitcoin blockspace is (from my perspective) a welcome one.

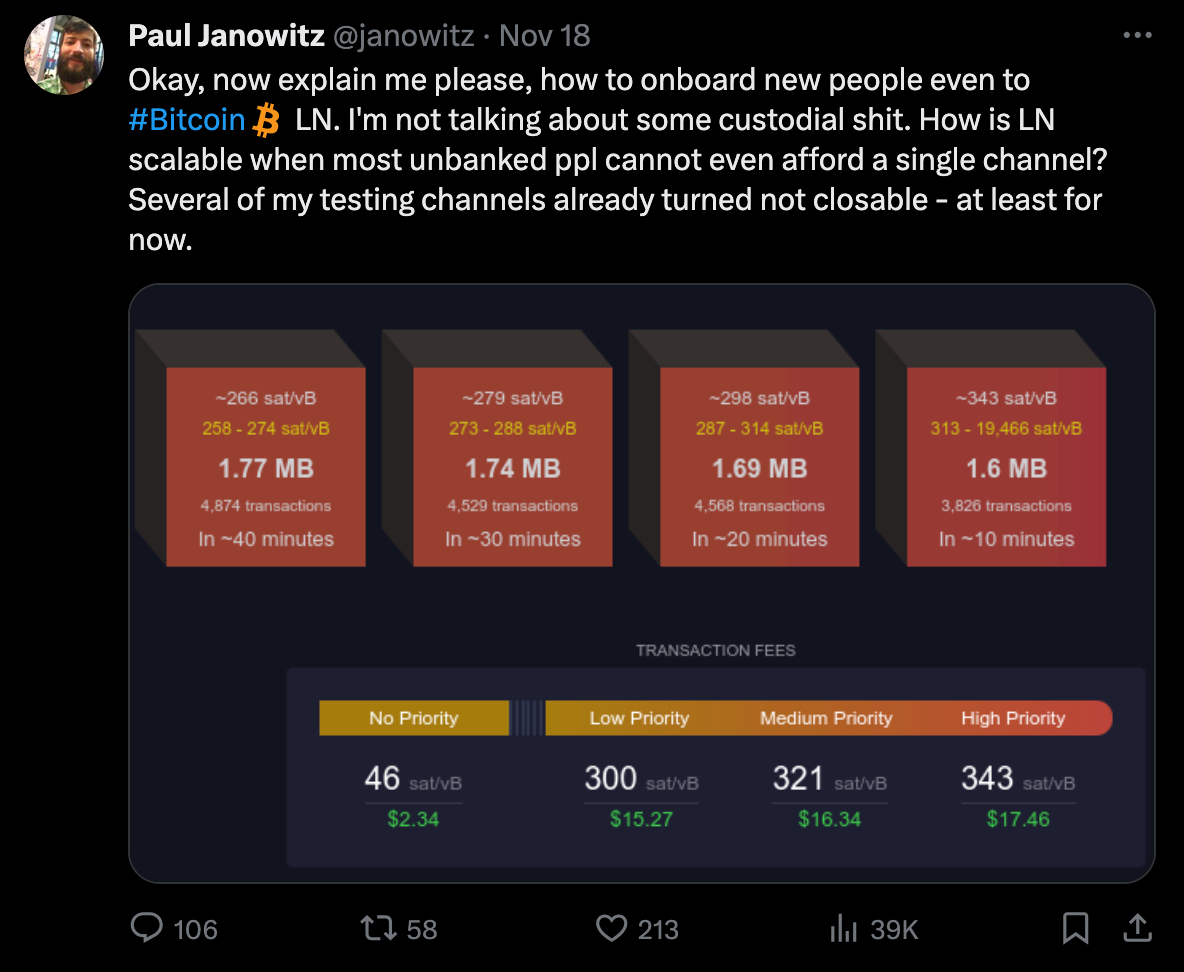

Not everyone feels the same way. High fees mean it is more expensive to use the network. For people who work or depend on cost-sensitive use cases like banking the unbanked in the developing world, higher fees are painful and frustrating:

Most of this new demand is for ordinal inscriptions, which we’ve talked about before. Ordinal inscriptions are (very briefly) a way of sticking arbitrary data into the witness of a transaction and then associating that arbitrary data with a particular satoshi.1 There are (in theory) many ways to use inscriptions, but the main use case so far has been Bitcoin NFTs and BRC-20 memecoins.

Both of these are different ways of using blockspace as a resource directly. Bitcoin NFTs are vanity objects that flaunt the owner’s ability to pay for the space used to inscribe them. BRC-20 tokens are minted using proof-of-wasted-blockspace for distribution.2 The details differ but they both take up blockspace that would otherwise have gone to more traditional bitcoin transactions.

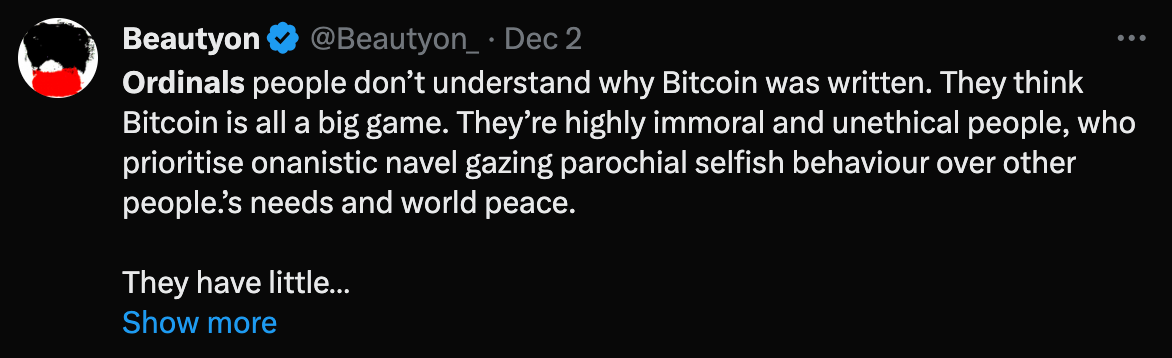

Effectively, an underground casino has emerged on top of Bitcoin and is using blockspace to build slot machines, pricing out other more cost-sensitive transactions in the process. To some people, using Bitcoin transactions to power an imitation DeFi economy is ontologically evil, a corruption of Bitcoin’s true purpose and a displacement of other more legitimate use cases:

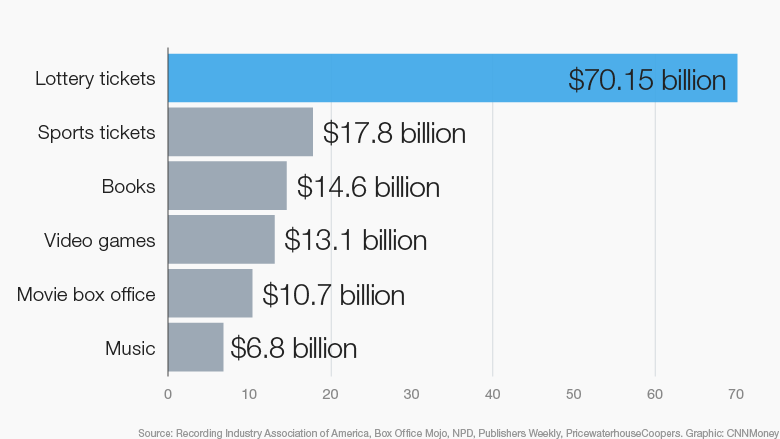

It’s perfectly reasonable to consider gambling on frog pictures a less worthy use of scarce blockspace than helping people escape poverty — but the Bitcoin network does not prioritize transactions by moral worth. It prioritizes by market demand, and the market demand for gambling is enormous:

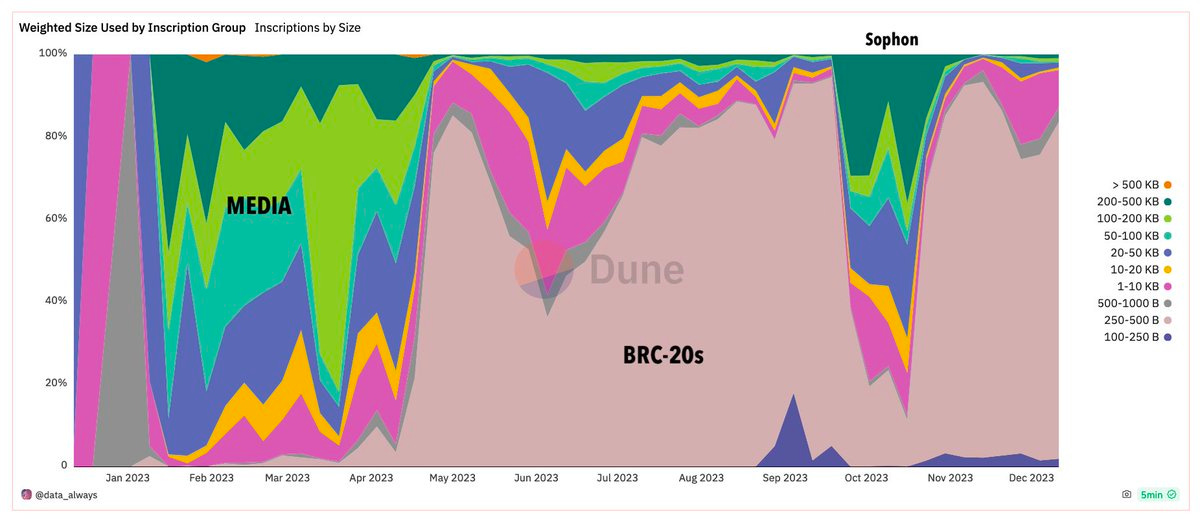

NFTs are already a symbolic flashpoint, so they naturally draw a lot of focus in the conversations about ordinals, but in practice image inscriptions are large and expensive and have mostly been priced out by smaller, text-based inscriptions like those that create new BRC-20 tokens.3 You can see that pretty clearly in this graph of inscription types over time — the colorful stripes represent larger inscriptions that are quickly squeezed out by smaller text-based BRC-20 inscriptions.

Every new generation of use cases crowd out the previous ones (or make them more expensive). Demand for Bitcoin blockspace keeps growing with every new user and use case, but the supply is perfectly unyielding. Tick-tock, next block.

This is actually not the first time that gambling transactions have dominated the Bitcoin network: at one point in 2013 more than half of all on-chain transactions were coming from SatoshiDice. Similar to the debate over ordinals today, many people considered SatoshiDice to be a denial of service attack on Bitcoin.

Bitcoin developer and extremely weird dude Luke Dashjr once tried unsuccessfully to filter out gambling transactions from places like SatoshiDice as 'spam'. Old habits must die hard because almost a decade later he is trying to censor frivolous gambling transactions by configuring his Ocean mining pool to exclude inscriptions from blocks they build. This gesture is largely symbolic, since inscriptions just end up included in the next block anyway — but it does come at a cost.

At time of writing Ocean has found 2 blocks (meaning it has done little to stem the tide of inscriptions) and it gave up ~1% of fees that would have come from the excluded transactions. Ocean was probably hoping that taking a stand against inscriptions would attract ideologically aligned miners to its new pool, but that doesn’t seem to have happened yet — they’ve already had to walk the policy back and make it and optional choice for miners. In general Bitcoin mining is an extremely competitive business with razor thin margins, it’s not clear there is appetite for a pool that gives up revenue in order to mildly inconvenience gamblers.

Reasonable people can disagree about whether inscriptions are actually healthy for the network. For one thing, it is important for fees not just to be high but to be relatively steady — if the fees are too volatile it might be more profitable for miners to fight over control of a particularly valuable block than to build on top of it, which could potentially destabilize the network.4

More subtly but probably more importantly, inscriptions increase the surface area for miner extractable value (MEV) in Bitcoin. I’ve written about MEV in more detail here, but the basic idea is that miners are trying to do anything they can to profit from their authority over what transactions are confirmed and in what order. If the main thing they can do to profit is collect transaction fees the incentives are clear and the network is predictable. But as transactions get more complicated, the opportunities for miners to profit get more complicated as well.

If getting the most out of MEV extraction requires sophisticated expertise, the network could end up centralizing on a handful of specialist experts — as is already happening on Ethereum. Previously the limited flexibility of the Bitcoin network also limited the threat of MEV — but inscriptions have shown you can use Bitcoin blockspace in unexpectedly flexible ways. That makes Bitcoin transactions more useful, but it also makes the network incentives harder to reason about.

Ultimately, whether inscriptions are good for Bitcoin or not it is better to find out sooner rather than later. If network security can be destabilized by the organic gambling behavior of degenerates Bitcoin was never going to survive an attack by motivated nation states. If moralizing weirdos can censor gambling transactions, governments will be able to censor transactions they don’t like, too.

If Bitcoin actually works as intended, there is no wrong way to use it.

Bitcoin itself doesn’t actually keep track of individual satoshis — the smallest unit the network pays attention to is the UTXO. Ordinals are a kind of 'meta-game' played on top of Bitcoin where the participants agree on certain conventions that decide which satoshis get assigned to which UTXOs when a transaction is made. Ordinals (and ordinal inscriptions) are an independent Schelling point whose rules are still actively being established, which causes interesting corner cases like cursed inscriptions.

Bitcoin distributes new coins (and blockspace) to anyone who provably sacrificed computational resources to the network by mining. Proof-of-wasted-blockspace distribution does something economically equivalent by distributing coins to anyone who provably sacrifices blockspace. That means the distribution is 'fair' in the sense that anyone can participate and no one is given any special advantage in the initial distribution. The technique was first pioneered by the HEX inspired ponzicoin XEN.

For a brief while ordinals developer and Taproot Wizards CTO Rijndael (@rot13maxi) ran a service called Sophon that was essentially suppressing BRC-20 mints by front-running any new mints and stealing their tickers. He stopped funding the service and open-sourced the code but no one else has seems to have stepped up to run it in his place.

In the Ethereum world trying to rewrite past confirmations is known as time banditry, which is frankly adorable.