How to kill a bank (and blame them for it)

How the Fed shoved Silicon Valley Bank off a cliff for their own good

How to kill a bank

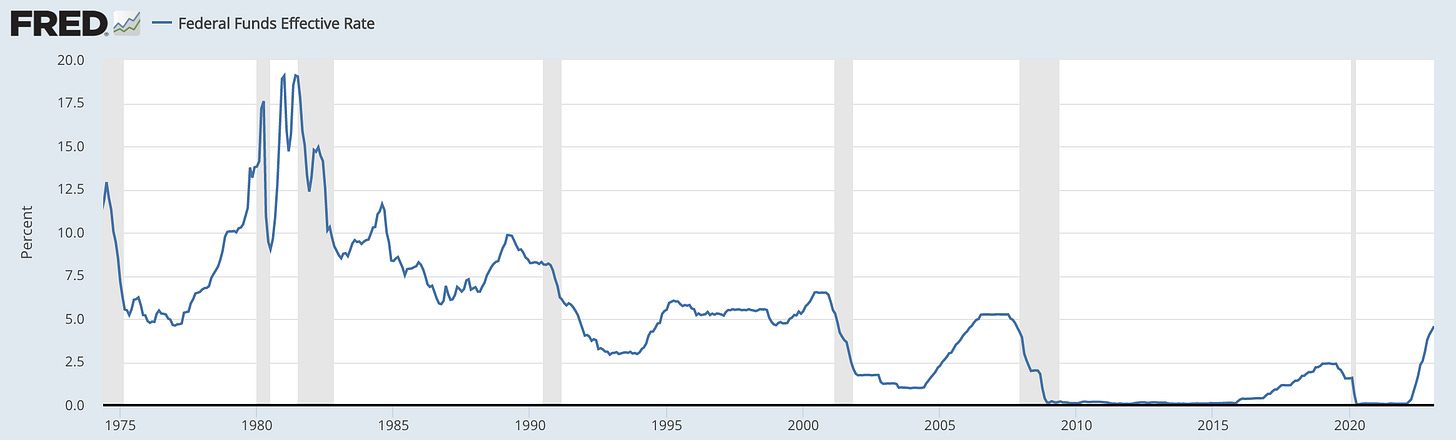

This is a graph of the Federal Funds rate, the effective interest rates that banks pay to borrow from each other overnight:

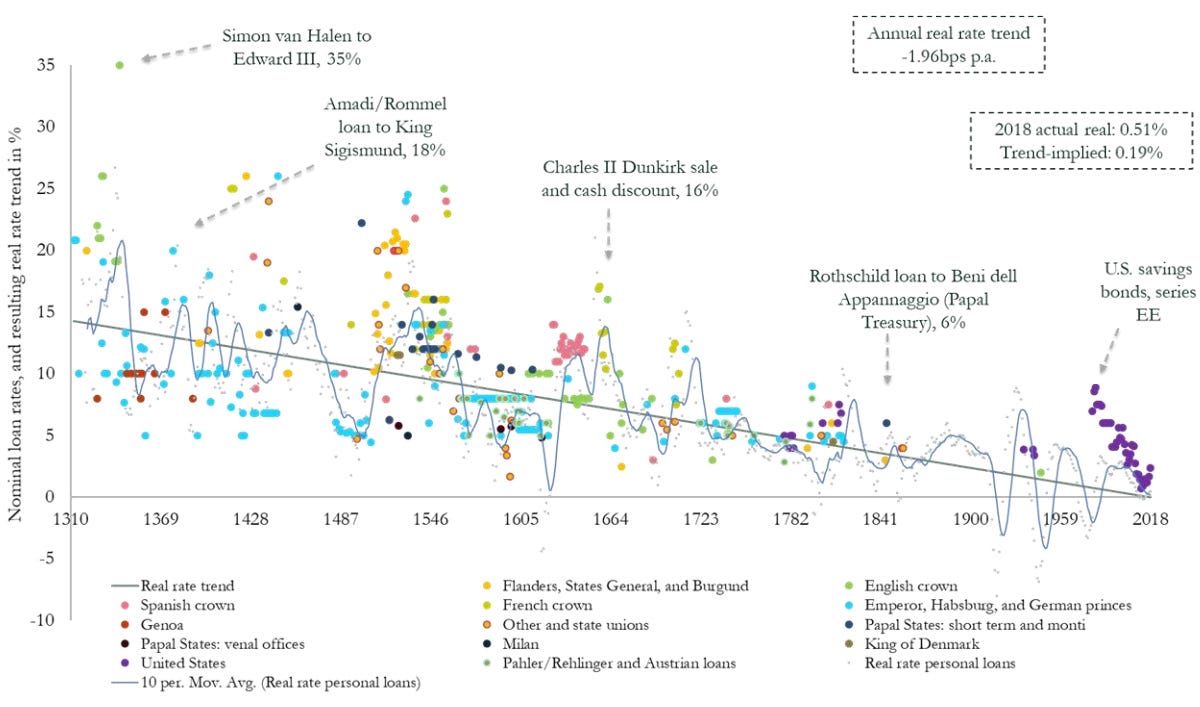

Since the Federal Funds rate is how much banks are paying to borrow funds it represents something like a lower bound on interest rates in the economy at large. There are a couple of things that stand out about the history of the federal funds rate. First, interest rates have been more-or-less falling for the last forty years.1 In the 2008 financial crisis interest rates collapsed to zero and then stayed there for most of the last two decades, briefly climbing up in the late 2010s only to be slashed back down to zero as a response to Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020.

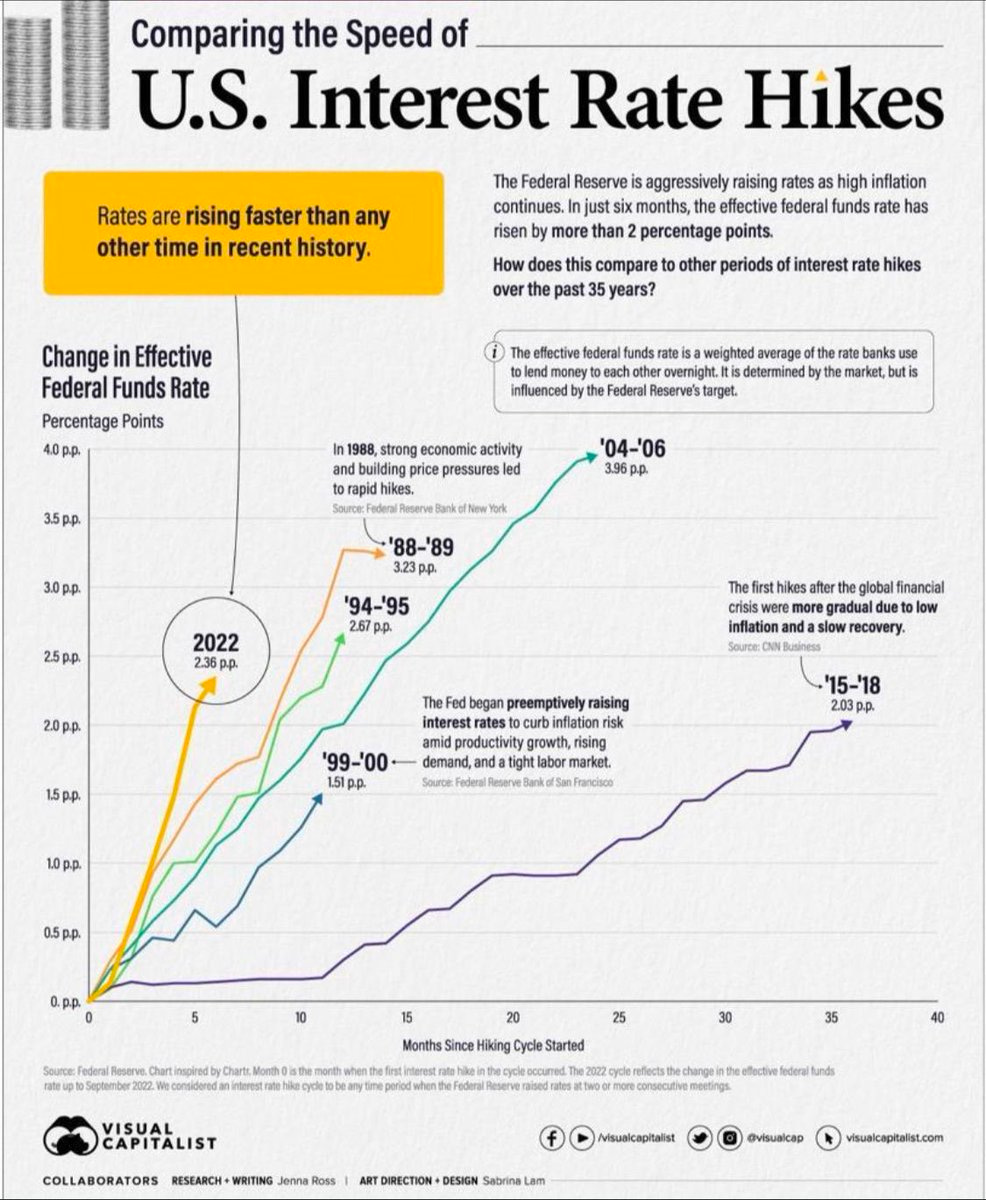

Recently the Fed has been raising rates again in response to growing concerns about inflation. The Federal Fund rates aren’t really that high by historical standards but this has been the steepest climb in interest rates since the 1980s — and since changes in interest rates are relative rather than absolute the actual impact of these hikes are much larger. The rise in rates in 1981 from ~10% to ~19% was a ~2x increase, the rise in the last year from ~0.25% to ~4.5% was an ~18x increase. In other words, the U.S. banking sector spent most of the last two decades flooded with money by the lowest interest rates in history and then over the last twelve months crashed directly into the sharpest rate increases in history.

Lots of things happened in the era of zero interest rates. Low rates meant it was easy to get money, which meant there was a lot of money chasing a (relatively) small number of available investments. Investors had to take on more risk to get the same expected return. The market became more speculative. Tech unicorns became more common. Tesla’s valuation skyrocketed. Meme stocks became a thing and then eventually dogecoin, NFTs, etc. The mechanisms are complicated but the high level overview is pretty straightforward: two decades of artificially cheap money turned financial markets everywhere into a casino for the insane.

All that cheap money also meant there were lots of well capitalized startups with large cash balances they needed to store somewhere. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) of Santa Clara specialized in offering financial services to those startups. That was a very lucrative business for a while! But it turned out to have some disadvantages.

Lots of startups with lots of money meant that SVB had lots of deposits, but it also meant most of its customers were quite flush and didn’t need loans. So SVB had a lot of cash sitting idle on their books. To make those deposits more profitable SVB bought US Treasuries and mortgage backed securities — basically to earn interest on their large, idle customer deposits.

US Treasuries are generally very safe investments — the US government is almost certainly not going to default on its debt. But that safety only applies if you hold the Treasury until maturity. If you hold a Treasury until it matures you are betting on the US government to pay its debts (very safe), but if you sell a Treasury before it matures you are betting on whether the US government will be offering higher rates when you sell than when you bought (not safe at all). If interest rates are falling people will pay you a premium for the high interest rate you have already locked in on your Treasury — but if interest rates are rising the value of your Treasuries (and their low rates) will go down. If interest rates go up at the fastest speed in history, anyone who owns lots of Treasuries is going to have a bad time.2

That meant those rapid hikes were very bad news for Silicon Valley Bank. The trend of sky-high valuations and enormous investment rounds in the tech industry waned and new deposits started drying up. At the same time rising rates meant their portfolio of ~$80B of long-dated (>10 year) bonds were plummeting in value. That wasn’t an issue of solvency because those assets were still an extremely safe bet to pay out at maturity. But it was a liquidity issue, because maturity was still a decade away and people are allowed to withdraw their deposits anytime they felt like it.

So SVB was in an extremely awkward position. The era of cheap money had pushed them into making a bet on low interest rates that ended up backfiring when the Fed reversed course and started hiking. Ultimately they decided to sell some bonds at a loss to make sure they had enough liquid cash available. They sold ~$21B in treasuries and mortgage backed securities, realizing ~$1.8B in losses. That’s a lot of money, even for a bank! SVB’s revenue in 2021 was only ~$1.5B. They also announced a plan to sell ~$2.3B in shares to cover those losses. They probably should have been more careful about how they announced it.

It’s easy to say with hindsight but it turns out that "nobody needs to panic unless somebody panics" was not the ideal message to reassure a nervous customer base. Instead it signaled the start of a bank run. VCs began advising portfolio companies to withdraw funds as quickly as possible and by the end of the next day the FDIC had announced the official failure of Silicon Valley Bank.

What happens next?

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures depositors on accounts up to $250k in value, but most of Silicon Valley Bank’s deposits (~97%) were in uninsured accounts or in insured accounts but above the $250k limit. It is tempting to think of that money as the surplus wealth of VCs and tech entrepreneurs that don’t deserve protection, but it isn’t quite that simple.

Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th largest commercial bank and it had ~40k active customers, mostly small businesses. SVB owned regional banks in Boston, Canada and the UK and it also handled payroll operations for many other businesses. The average salary of the people who are impacted by payroll failures is ~$48k/yr. Obliterating these accounts is effectively like firing tens of thousands of ordinary people who had no ability to choose the banks they relied on. But even more concerning than that is that SVB is not alone. Around ~50% of US deposits are in small banks and ~33% are in uninsured accounts.

The FDIC isn’t legally obligated to save uninsured SVB accounts — but they are obligated to prevent bank runs as best they can. If they let the businesses that banked with Silicon Valley Bank die, the risk is that everyone will flee other midsize banks and move their deposits into the handful of banks that are officially too big to fail. That may already be happening whether the FDIC intervenes to protect SVB depositors or not:

Most likely the FDIC will not need to "bail out" Silicon Valley Bank. Given that SVB’s problems are issues of liquidity rather than solvency there should be plenty of interest from larger banks in acquiring their assets in a fire sale. Already hedge funds are purportedly offering $0.60-$0.80 on the dollar for SVB assets. Finding a buyer is probably not a problem. That’s not the real question.

The real question is whether or not this is the start of a broader panic.

Other things happening right now:

You may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like:

It was probably irresponsible of SVB to take on as much duration risk as they did, but it wasn’t face value crazy. At the time SVB were acquiring (2021) most Fed presidents were predicting <0.75% rates and all of them were predicting <1%. Rates are now 4.75%.