The psychedelic garden blooms

Part II in our ongoing series about how the pyramid scheme reinvents itself over and over in crypto

In this issue:

The end of our cypherpunk innocence

ERC-20 and the implosion of the DAO

The Simple Agreement To Dump on Retail Investors

The rise of Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

The battle to unseat Ethereum

The madness of boredom

Where do we go from here?

In recent weeks the number and diversity of new coins and new financial schemes has started to hit a fever pitch very reminiscent of the height of the ICO era. A number of readers reached out to ask variations of "How did we get here?"

This is the second in a series tracing the history of fund-raising in crypto from the Bitcoin whitepaper to the rise of TikTok memecoins. In the first section we talked about the early history of alt-coins through the Ethereum ICO and the dawn of the Smart Contract era. In this section we’ll discuss the year of ICOs, the rise of DeFi and the ever accelerating feedback loop of ponzinomics.

The end of our cypherpunk innocence

The early success of Ethereum caused several things at once:

Ethereum’s founders had gotten rich, which drew new founders to the space.

Ethereum’s investors had gotten rich, which drew new investors to the space.

No one went to jail, which lowered perceived legal risk for new projects and brought Silicon Valley VC money into the space.

Ethereum was easier to build on, which lowered development cost.

Ethereum showed it wasn’t worth trying to compete with Bitcoin on its own terms but that it was better to advertise yourself as something entirely different.

These days we think of the cryptocurrency space as being all about money but in the early days there was a long time when Bitcoin was worthless and almost everyone involved with it was interested because of cypherpunk philosophy. Eventually as more and more wealth was created the conversation became a volatile mix between those motivated by money and those motivated by ideals. But pretty much everyone drawn in by the success of the Ethereum ICO came looking for opportunities to get rich. The financial view of cryptocurrency took over and has dominated ever since.

ERC-20 and the implosion of the DAO

The first and most obvious consequence of Ethereum’s success was a string of copycat launches that with various degrees of shamelessness sought to emulate and build on the success of Ethereum. Specifically the success of its fund-raising. Ethereum mostly tried to fuse an ambitious cypherpunk vision with an aggressive marketing strategy. Many of the projects that followed kept the cypherpunk marketing and aesthetic but did away with the expensive and clunky attempts to preserve a veil of decentralization.

On a technical level Ethereum was systematically lowering the barriers to entry for new cryptocurrencies. An early and powerful example was the ERC-20 standard - a shared definition of the basic functions of a token like transfer and check account balance. Prior to ERC-20 one of the biggest challenges for a new token was to convince exchanges they were important enough to bother listing, but now with the ERC-20 standard exchanges could effortlessly list new tokens with no additional work.

New projects didn’t even need to do anything - many ICOs sold vanilla ERC-20 tokens as placeholders for a promised platform that would supposedly be built with the funds raised in the token sale.1

The serpent almost immediately began to swallow itself - in April of 2016 a crowdfunding campaign for the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) raised ~$150M worth of ETH, approximately ~14% of all ETH at the time. The DAO was one of the largest crowd-funded projects in history. It was intended to be a decentralized venture fund whose owners could submit and vote on possible investments to make with the funds raised. It lasted a little under two months before an attacker used a recursive exploit to drain ~3.6M ETH (~$50M at the time).

The saga that ensued is its own lengthy drama but to summarize it briefly here the Ethereum founders used their influence with the community to organize a fork that returned the stolen funds and dissolved the DAO. Ethereum’s price suffered for a while but was back to finding new all time highs by September. The market did not lose its taste for making new cryptocurrency investments.

The Simple Agreement To Dump on Retail Investors

The ERC-20 protocol had made it easy to launch and sell a new token and the DAO had shown the appetite for those investments was still huge even in the face of significant risk. On top of that the SEC still had taken no action making the legal risk seem smaller and smaller. Token sales got larger and more sophisticated.

Silicon Valley VC firms began backing token projects using the Simple Agreement for Future Tokens (SAFT). The goal of the SAFT was to (a) let VCs buy tokens at cut rate pre-market prices and (b) create a thing which was very obviously a security (and therefore tightly regulated) so that hopefully regulators would conclude tokens must not be a security (and therefore safe to sell to the public). In practice the main effect of the SAFT was that VCs provided funding to token markets and then sold their discounted stake off to the public at face value.

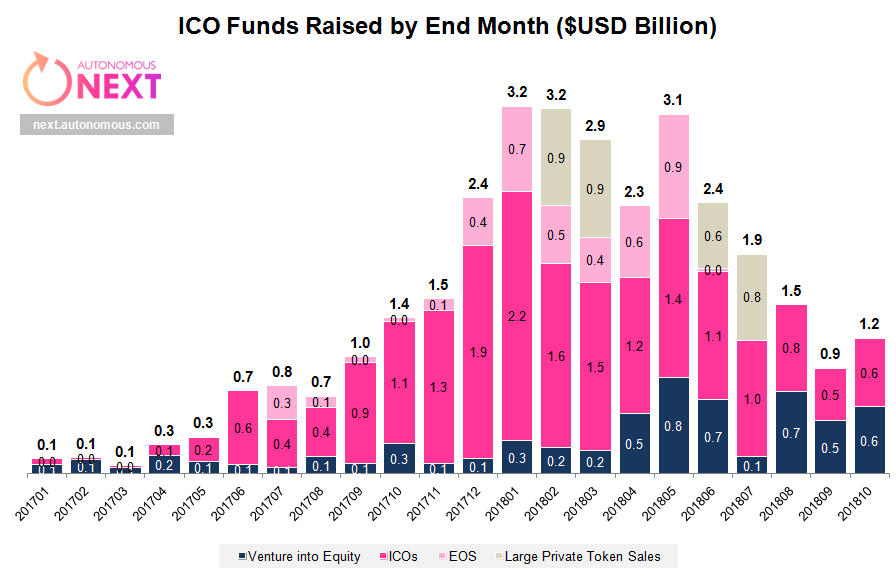

By the beginning of 2017 ICOs were raising billions each month, mostly from unaccredited retail investors.

By 2018 this cycle had been going on for long enough people started to notice that almost none of the projects were delivering on the hype they had launched with - either in price or in functionality. Many projects had failed technically or organizationally, while others languished. Some had been outright abandoned by developers who were already rich at launch and didn’t actually need to deliver on their promises anymore.2 Interest in buying into new cryptocurrencies waned.

Eventually the SEC made clear that the ICO structure was an illegal securities sale and fined a handful of the organizations that had done one. For the most part clarity from the SEC came well after the momentum behind ICOs was already fading though - and the fines themselves were insignificant. The SEC fined the company Block.one for their crowdsale of the EOS token - but the sale raised ~$4.1B and the SEC only fined Block.one ~$24M, or about ~0.5%. Barely an operating cost. It didn’t get around to filing a complaint against literal ponzi scheme Bitconnect until years later.

It is reasonable to presume that future enforcement will be stricter now that the SEC has made their stance on ICOs clear, but the truth is the ICO mostly died under its own weight before the SEC ever got around to doing anything about it.

The rise of Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

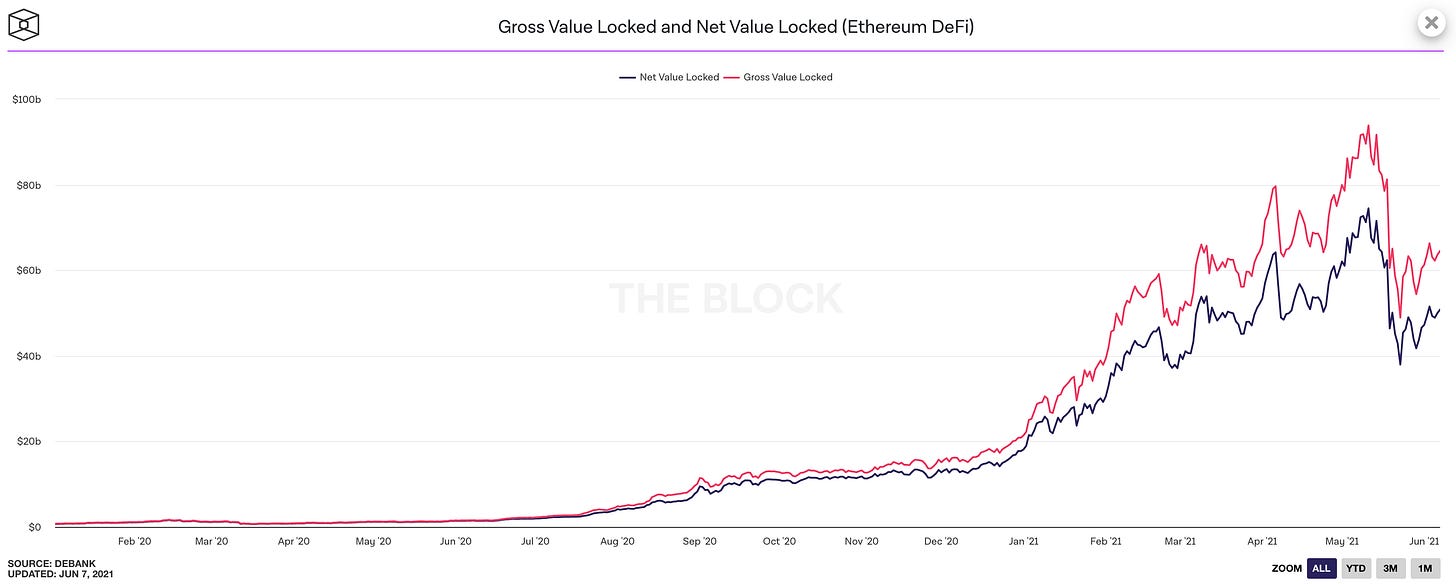

The market was not tired of investing in crypto - but it was marginally more wary about investing in pitch decks. There was still just as much capital looking for projects to fund, but now it was seeking interesting demos and prototypes alongside grandiose, all-encompassing vision. Where the previous generation of ICOs were generally raising money to fund development, this new generation of projects were using development as a means to attract money.

These new smart contracts (mainly built on Ethereum) were collectively known as decentralized finance, or DeFi. Each one represented a new parlor trick that one could perform by investing capital - some more profitable than others. Decentralized exchanges (DEX) paid investors to provide liquidity as automated market makers for new token markets. Stablecoins paid investors to back overcollateralized loans. Yield farms paid investors to deploy capital dynamically to the highest paying trades.

Many of these projects were good faith efforts to build legitimately useful financial products - others were not. Three of the first six smart contracts deployed to the Ethereum blockchain were pyramid schemes. Up to this point in cryptohistory everyone knew that many of the participants were uninformed gamblers just having fun - but relatively few would admit it out loud, especially about themselves. With "cryptographically fair" pyramid schemes the scam was out in the open and you could embrace it. The gambling subtext could finally become text.

New tokens didn’t necessarily need to tell a story about why they would eventually be useful anymore. They just needed a story about why the price would go up. Pyramids, ponzis and quasi-lotteries like Fairwin, Forsage, PoWH3D and Fomo3D have at various times dominated the network by both traffic and scale. Many modern NFT projects differ from these early lotteries only in aesthetic packaging.

Its relatively easy to design a set of rules that trick people into irrational investments - the dollar auction is one of my favorite examples. You can be perfectly honest about how a game works and still convince people to make bad bets. It turns out that in a transparent but permissionless marketplace like DeFi the first businesses that spring up are casinos. They thrived not just because the blockchain is permissionless but because the community was so flush with newly wealthy, highly confident risk takers eager to make their next big investment.

Not everything in DeFi is a casino but it is difficult to draw a clean line dividing the casinos from the rest of the DeFi economy. The two largest applications of capital on DeFi are lending protocols followed by market making for DEXs - together they account for the vast majority of the actual DeFi economy. Both are legitimate financial products in their own right, but also beneficiaries of the vibrant market for gambling tokens. The DeFi casinos create a lot of trade volume for DEXs and a lot of demand for credit from lending protocols. It is still unclear how much of the DeFi economy is recursive, with speculators chasing yield that is ultimately paid by speculators chasing yield.

What is very clear is that it is successfully attracting capital.

The battle to unseat Ethereum

In the early days of crypto developers launched many Bitcoin clones with slight variations, probing for a version that might have a competitive edge. Competing with Bitcoin on its own terms (limited supply, censorship resistance, etc) proved largely unsuccessful. Instead of money, Ethereum framed itself as a smart contract platform and rallied investors toward a different set of core values: functionality, composability, ease of development, etc. Ethereum had found a way around the Bitcoin moat - but it hadn’t necessarily found a moat of its own.

When Ethereum launched it divided the crypto community into those who thought base layer blockchains should be extremely minimal (Bitcoiners) and those who thought they should be Turing complete (everyone else). But it also divided the Turing complete crowd into those who built on Ethereum and those who competed with it. While the former built the DeFi economy the latter experimented with tweaking Ethereum’s parameters probing for weakness, just as they once did with Bitcoin.

A particularly pure example of that pattern is Tron - a fork of the Ethereum codebase predicated pretty much entirely on the idea that Ethereum had left money on the table by not advertising enough in Asian markets. Justin Sun (the founder of Tron) plagiarized the Ethereum whitepaper and slapped a couple of different codebases together over a weekend in 2017 to raise ~$70M. Since then Tron has mimicked Ethereum’s development path and functionality but with an emphasis on cheap fees and flashy marketing over decentralization.

Some applications (like Tether, for example) care a lot about fees and very little about decentralization. You can see Tether migrating away from the (relatively) expensive but (relatively) decentralized networks towards the cheaper, more centralized options:

This is the shape of the competitive threat to Ethereum: decentralization is expensive, especially for decentralized apps. How much do you really need? It turns out Tether doesn’t need very much decentralization in practice, so it is getting priced out of Ethereum just as it was once priced out of Bitcoin. An important and still unanswered question is: how much decentralization do speculators need? Are they investors who see decentralization as a key fundamental attribute?

Or are they gamblers happy to migrate to the casino with the cheapest fees?

The madness of boredom

The financial crash in March 2020 in response to the widespread pandemic lockdowns threw every financial market into a tailspin at once - but it also had a more subtle, pernicious effect on the markets. In a world without bars, theaters, nightclubs and most importantly casinos - people were bored. Many of them turned to daytrading apps like Robinhood for entertainment - and when enough people treat investments as a slot machine the price of things can become truly chaotic.

Matt Levine calls it the "Boredom Market Hypothesis" - the idea that if enough of the market is investing for fun rather than for profit prices can become completely detached from the underlying asset they represent. This is the climate that caused meme stocks like Gamestop, AMC and Hertz to skyrocket. It is the environment that took Dogecoin to $0.70/DOGE. It is the world where Elon Musk can double the price of a company by tweeting that he likes Baby Shark. It is the age of TikTok investment advice gurus. The gods have gone mad.

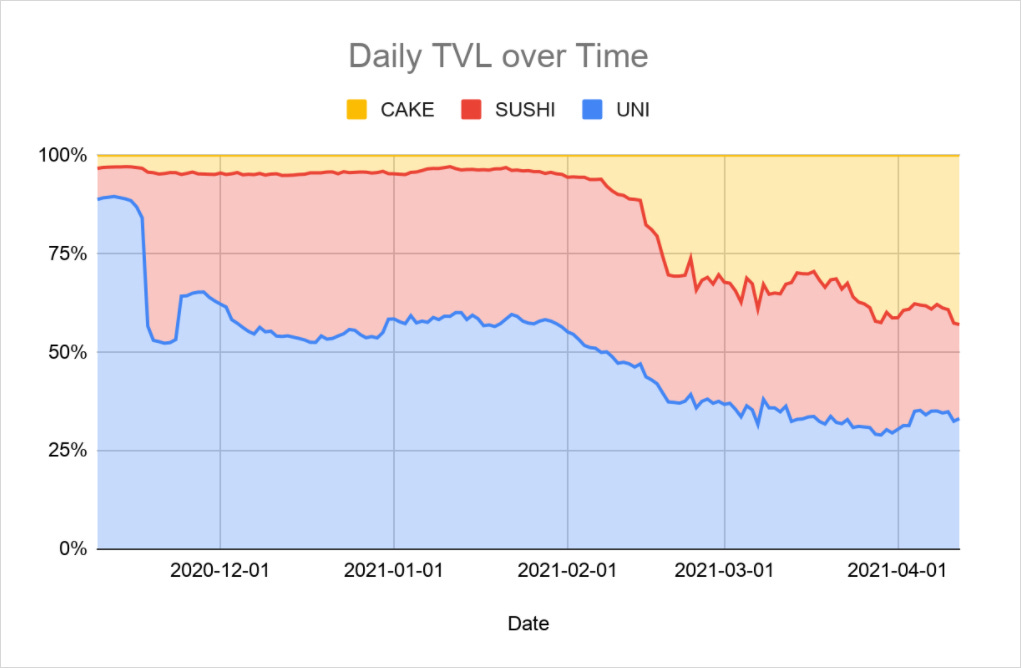

It is against this backdrop that the Binance Smart Chain (BSC) launched in May of 2020 and began to systematically compete with Ethereum by mimicking functionality, compromising on decentralization and drastically undercutting fees. BSC is fully compatible with the Ethereum Virtual Machine, meaning it is easy to port dApps from Ethereum to BSC.

The apps that migrate benefit from reduced fees (at the cost of reduced censorship resistance). The apps that don’t migrate just get cloned. The result is that BSC has a fully-featured mirror copy of most of the major DeFi projects, either ported or cloned - and many of the clones have flourished in a low-fee environment, often growing much more quickly than their ancestors. Compare the market share of decentralized exchanges like Uniswap (an Ethereum based DEX) and SushiSwap (an Ethereum based clone of Uniswap) to the market share of PancakeSwap (a BSC based Uniswap clone):

BSC is the apotheosis of this decade long journey away from the monastic ideals of Satoshi. It is not decentralized and does not aspire to decentralization - it is named after the company that founded it. The applications that run on top of it are shameless clones - often finding themselves victims of known exploits that they ported over with their copied code. The money sloshing around in crypto has now found its way into the purest instantiation of the digital casino: r/cryptomoonshots

r/Cryptomoonshots is a community dedicated to "low market cap cryptocurrencies with a moonshot potential" - a group of gamblers who are purists in their pursuit of numbers that will go up. The tokens discussed there are touted for their memetic potential or their ponzi-like rules that punish selling and reward holding. There is no discussion of utility or eventual practical value. Probably their most important competitive features are their names: SafeMoon, SaferMoon, SafeMars, FuckElon, PinkMoon, CHAD, etc, etc.

To watch the r/cryptomoonshots feed is to gaze into a roiling, recombinant id - chopping each submission into its component traits and reassembling them into endless different arrangements. It is the financial equivalent of Elsagate, the strange froth of algorithmically-generated animated videos targeting young children on YouTube in 2017. They are a twisted funhouse mirror reflecting the concepts and aesthetics that attract casual investors hoping to buy a winning lottery ticket.

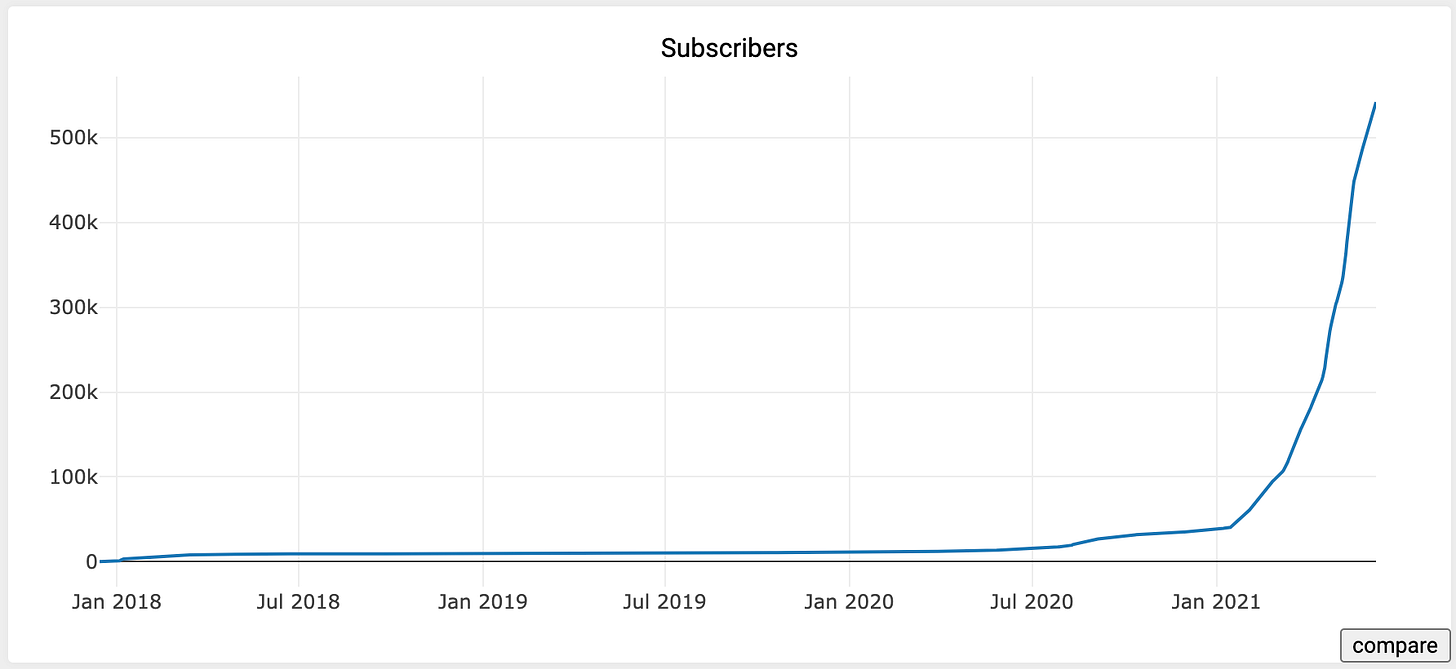

Every project is doomed to relatively rapid failure, but new projects replace them faster than old projects die off and the space as a whole continues to grow:

Where do we go from here?

The rolling crescendo of ponzicoins that we are seeing today is not caused by Bitcoin or by cryptocurrency in general but by a failure of our regulatory agencies. Truly decentralized coins are able to resist centralized control - but that defensive strength is expensive and those expenses naturally limit the growth of the casinos and ponzis we see in low-fee platforms like BSC.

What is needed is not new laws aimed at cryptocurrencies but rather more consistent and complete enforcement of the regulations that already exist. Pundits and politicians like to use fringe DeFi projects like SafeMoon as damning examples of the whole space, but in truth the projects with the most resistance to government control are also the most expensive and idealistic and the least likely to be useful to mercenary gambling projects like SafeMoon. The most excessive projects in the space (in terms of risk to retail investors) are also the most centralized and therefore also the easiest to shut down.

Startups masquerading as decentralized protocols should be forced to commit to decentralization or submit to government control. Before we as a society start attempting to draft and enforce crypto-specific laws, let’s make at least a half-hearted attempt to enforce the laws that we already have in the ways we easily can. If we don’t enforce our existing rules, what impact could new ones be expected to have?

In the meantime let’s all take a moment to be grateful to Satoshi. He had the chance to be orders of magnitude greedier than any of the hucksters that followed him and chose to take a higher path instead.

In fact a lot of tokens planned to compete with Ethereum after they finished using it to fundraise which feels like poor manners.

This is why traditional startups pay in equity and why that equity usually vests over time - to keep founders and employees interests aligned with shareholders. For the most part that was not the case with ICOs.