Does the Merge mean proof-of-stake works?

What can we learn about Proof-of-Stake from watching Ethereum actually run it?

Inside this issue:

Does the Merge mean proof-of-stake works? (reader submitted)

So is proof-of-stake decentralized?

How decentralized is decentralized enough?

Did proof-of-stake help the environment?

So to return to your question …

Does the Merge mean proof-of-stake works?

"A question I’m curious for your take on: does the successful merge of proof of stake show that the approach at least 'works'? It has obvious problems with centralization, but maybe there are still a lot of use cases where centralization is fine?" — AK

That’s a very fair question. Regular readers of Something Interesting will be familiar with my dislike of proof-of-stake, but the Merge was an enormous event in crypto. New information of that magnitude is always a good reason to re-examine and update your beliefs. So does the Merge show that proof-of-stake works?

There are actually a lot of things we could mean asking if proof-of-stake works. For example, we could mean does the code literally work, as in does it successfully process transactions without forks or network crashes? The answer here is clearly yes — the Merge was almost eerily smooth for such a massive engineering change in an adversarial system with no downtime. That is a genuinely remarkable feat.

Another thing we could mean by that question is, does the resulting system achieve our intended goals? Does proof-of-stake provide decentralized consensus? Is proof-of-stake better than the proof-of-work system it replaced? These questions are obviously a bit more complicated. To ask whether proof-of-stake is achieving our goals we have to know what those goals are. What are we trying to do here, exactly?

Both proof-of-stake and proof-of-work are strategies for achieving decentralized consensus. In other words, they are ways for nodes on a network to agree on the state of the network (consensus) without any particular nodes being in control (decentralized). Nobody really disputes that Ethereum is achieving consensus. Transactions are clearing, smart contracts are processing. You can buy and sell things on the network. So in that sense proof-of-stake is definitely working — whether it is decentralized is more difficult to say.

A network is decentralized if it has no central authority. Decentralization is often treated as automatically desirable in the crypto industry but in most situations it is actually a design flaw. Central authorities make coordinating a network cheaper, faster and more flexible — in other words, decentralizing a network makes it more expensive, slower and less flexible. It’s not usually an advantage at all!

Decentralization is bad in pretty much every way except one: no central authority means no one is in control. No one can withhold permission to access a decentralized network and no one can impose new rules on it. Proof-of-work and proof-of-stake are both tools for preserving the rules of the systems they protect.

One way to think about decentralization is as an absolute binary: either a central authority controls the network or it does not. But this definition is backward looking (has a central authority seized control) as opposed to forward looking (could a central authority seize control). There is no comforting binary looking forward because there is no way to know how much security is "enough."

How strong a defense must be to secure the network is a function of how motivated the attacker is. A technically stronger defense that triggers ideological opposition might actually be less secure — or a technically weaker defense that successfully intimidates would-be attackers might be more secure. The security of a decentralized network is an empirical question, not a theoretical one. There is no other way to learn than to put a system into use and see if it survives.

This is the experiment that is taking place on Ethereum today.

So is proof-of-stake decentralized?

I think reasonable people can still disagree about whether proof-of-stake is successfully keeping the network decentralized.

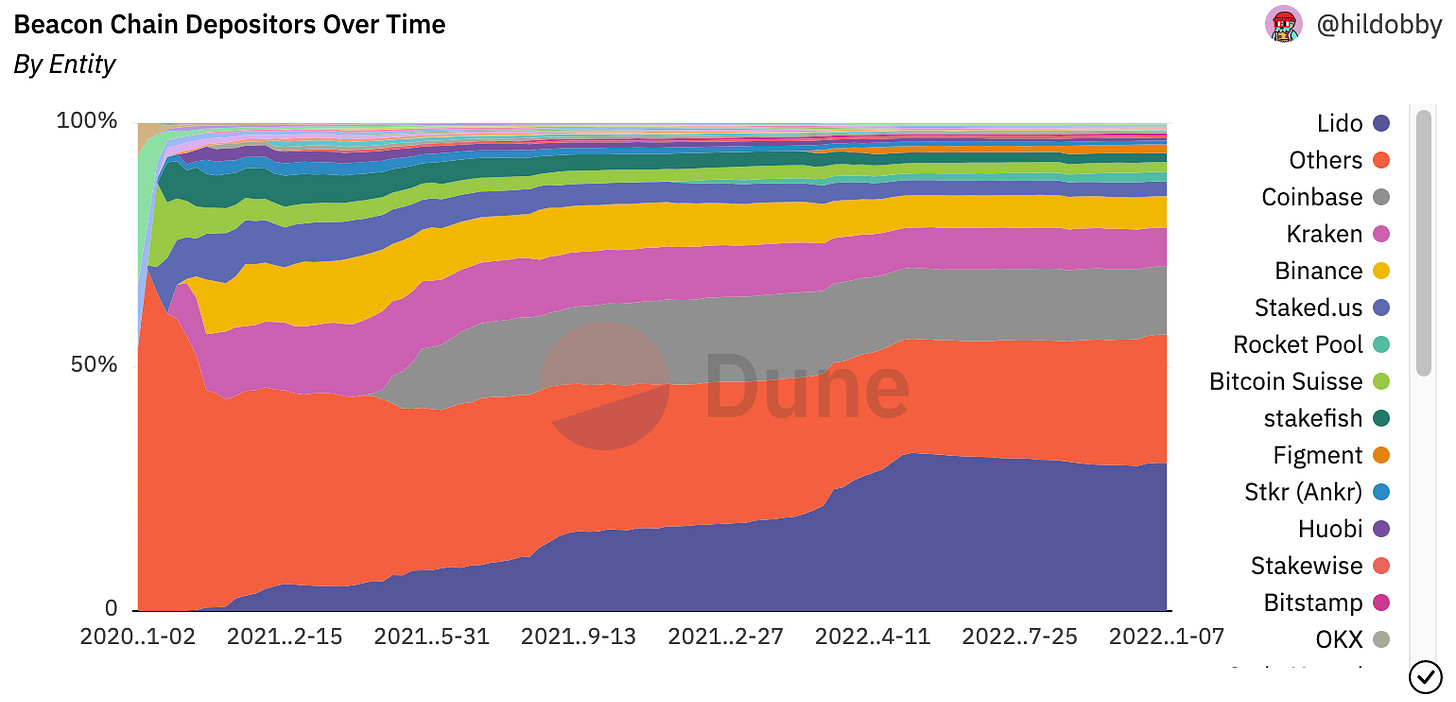

We’ve talked before about the threat of liquid staking and the risk that network effects will naturally cause staked capital to accumulate under one or two validators and effectively centralize the network. It’s probably too early to make predictions about the long term trends here but the inexorable growth of Lido has at least slowed down since we wrote about it in June. At time of writing the top three validators (Lido1, Coinbase & Kraken) control ~52.3% of staked ETH.

Unfortunately you can’t observe decentralization directly, you can only notice the absence of central control. The clearest evidence of that absence right now is probably the OFAC sanctioning of Tornado Cash earlier this year. Usage of Tornado Cash is way down since before the sanctions went into effect but the smart contract is still operational. No one is censoring the Ethereum network today — circumstantial evidence implying that it is still decentralized.

But not every ETH validator is choosing to validate Tornado Cash transactions. Since the Merge the share of validators enforcing OFAC compliance has risen steadily:

Deciding what this graph might mean for decentralization is extremely nuanced. OFAC compliant validators are still building on non-OFAC compliant blocks, which means no one is actively censoring the network — Tornado Cash transactions are just taking a bit longer to confirm. But there are now enough OFAC-compliant validators that if they did decide to exclude those blocks for whatever reason they could. Of course it was always the case that a majority of the validators could conspire to censor the network — and so far no one is doing that.

The OFAC compliant validators in the graph above are most likely not regulatory enthusiasts — the real thing that unites them is a love of profit. The reason they are all complying with OFAC is because they are all using one of a small handful of specialist experts to extract the most possible profit from creating a block (usually known as MEV) — and those services are complying with OFAC. If thousands of nodes from around the world work together to build consensus about the state of the network but ~¾ of them outsource the work to a single company in Ohio it is hard to call the result decentralized. But so far it remains fairly permissive.

How serious a threat you think this is to the network depends on how you feel about a chain of hypotheticals: Will the US government demand stricter OFAC enforcement? Will MEV relay services comply? Will validators tolerate censorship to maximize profit? Will DeFi users rally to boycott censorship? Is the government more motivated to control DeFi or are users more motivated to defend it?

Proof-of-stake didn’t create the centralizing risks of MEV but as the graph above makes clear it did rapidly accelerate them. That’s because the proof-of-work miners competed in several ways (cost of energy, storage, hardware, etc) that proof-of-stake validators do not, so the remaining ways validators still compete (MEV extraction, cost of capital, etc) are magnified in relative importance. MEV extraction is now a much larger percentage of the bottom line.

How decentralized is decentralized enough?

For most networks the benefits of coordination outweigh the costs of control and they don’t need to be decentralized at all. Bitcoin is seeking to build a network that acts as money, so it needs to be decentralized enough to resist the control of nation states.2 It is reasonable to wonder if there are intermediate design spaces in between those two extremes where "some" centralization might potentially be useful.

But remember decentralization is not a desirable quality in a network, it is a painful trade-off that we tolerate in exchange for avoiding control. To achieve any measure of decentralization we sacrifice speed, cost and flexibility — if we leave behind a control system those sacrifices were pointless theater. Building a network with "some" amount of centralization is like wearing a ghillie suit with a fascinator hat.

Transaction fees on ETH are expensive because total available space on ETH is very limited. Total available space is limited because more space would make it more difficult/expensive to run a node and verify the network yourself. The cheaper and easier it is to verify for yourself that the rules of the network have been followed the harder it is for anyone else to change the rules. Making a network cheap for validators makes it expensive for anyone who wants to transact. Put another way, if you don’t mind centralizing the network a bit you can make it a lot cheaper to use.

A hybrid of a decentralized/centralized network is the worst of both worlds: expensive to use without being difficult to control. But it is also possible to be too decentralized: an empty blockchain would be costless to verify but also perfectly useless. The right amount of decentralization is just enough to dissuade attackers and no more.

One way to dissuade attackers is to attempt to be invincible, which is more-or-less the Bitcoin strategy. Another way is to be unimportant, which is the actual thing that protects most long-tail blockchains from attack. It is also possible there is a viable third path where a network is strong enough to deter a certain class of attacker and compliant enough to avoid the attention of another. You could imagine a world where Ethereum validators enforce OFAC-sanctions but never implement KYC controls and the US government could overwhelm the system but never bothers.

One problem with that strategy is trying to walk the tightrope of keeping the network valuable enough to pay for the heavy cost of decentralization but not so valuable that governments demand control of it. As the network succeeds at capturing share in the real economy the incentive to attack the integrity of the system grows. So a decision to tolerate some degree of central influence in the network is effectively a decision to limit the ambitions of how much value the network is capable of creating.

If you think the ultimate destiny of DeFi is to be a kind of lightly-supervised casino in a jurisdictional gray-zone this structure could make sense. Anything that grew large enough or powerful enough to gain geopolitical significance (Tornado Cash enabling North Korea to evade sanctions, e.g.) would be shut down but anything that was merely "bad" but not a matter of national security (dog token rug-pulls, Bored Ape thefts, etc) would be ignored and allowed to continue.

That scenario inherently implies that ETH will not be money (because money is geopolitically significant) but it still leaves potential room for ETH holders to profit. It’s an open question what governments would demand of ETH and what rules ETH holders would be willing to tolerate. Do ETH holders actually care whether ETH is useful for evading sanctions? Would they still care if it became clear that the supervised economy was the more profitable opportunity?

It’s also not clear how much demand there would still be for the DeFi casino in a world where the total upside is widely understood to be capped. If most of the people are there for unsupervised player-vs-player games of skill and chance then no harm no foul. But if most DeFi users today are participating because they believe DeFi is the future they may lose interest in a domesticated network even if the feature set doesn’t really change. Or perhaps the users of DeFi today are tiny and irrelevant compared to the potential market that could be served if a few small compromises were made to make big banks and governments feel comfortable and safe.

A network is ultimately only as decentralized as the average participant desires. If most of the users of a network desire decentralization and are willing to pay for it the network can stay decentralized — but if most of a network’s members are indifferent to decentralization or only see it as a path to profit they will naturally centralize the network over time as they seek to lower costs and reduce friction. Etherscan, MetaMask, Infura and centralized dApp front-ends are all naturally occurring points of centralization that emerged out of users prioritizing cost/convenience.

Maintaining a network in a moderately decentralized state is possible but naturally unstable, like balancing a wheel on top of a wheel. It requires everyone in the network to maintain individually separate but overlapping beliefs about which trade-offs for decentralization are critical and which are unnecessary. Eventually a moderately decentralized network will probably either be crushed by an attacker, abandoned by its users or move to a posture of full decentralization or full compliance. But there is no obvious way to predict how long eventually might take!

Did proof-of-stake help the environment?

A handful of proof-of-stake advocates argued for proof-of-stake on the grounds of network security but most have marketed it on environmentalist grounds by arguing that proof-of-stake uses less energy. I still think that’s a profound misunderstanding of both economic systems and environmental impact. Nobody turned off any power plants when Ethereum switched to proof-of-stake.

When a network spends $1M USD rewarding validators in an open competition validators will collectively spend $1M USD competing over that reward. Any competitors that aren’t willing to spend every marginal dollar competing will be outcompeted by other validators who are. Every marginal $1 spent securing the network will result in $1 worth of energy being spent by validators competing. I wrote a lot more about this phenomenon in How Bitcoin is like American Idol.

In proof-of-work that competition is easy to measure, observe and criticize because it is mostly contained within the system. In proof-of-stake that competition is pushed outside the network into things like MEV extraction and cost-of-capital, but that doesn’t reduce energy use it just makes it harder to measure, observe and criticize. That also means the network is buying security less efficiently since this more complicated / less observable competition is slower to optimize.

Proof-of-work advocates who think lowering the electricity bill for validators lowers the energy footprint of the network are wrong in two ways. First they are wrong because total energy use of the network includes lots of things outside the scope of direct electricity use. Second they are wrong because the total environmental footprint of a network should be measured in dollars not in watts. Comparing the impact of networks by raw wattage is a fundamental misunderstanding of both the economic and environmental meaning of energy.

Energy is not interchangeable. If it was we could solve all energy needs by setting off a few atomic bombs. In reality, some watts are useful and good (and hence fetch a high value in energy markets) and some watts are worthless (like sunshine on the Sahara) or even actively bad (like the energy in an explosive). That means unless you are a physicist the right comparison when comparing energy use across different times/places is not watts but dollars.

Once you realize that (1) a $1M reward to an open market will cause $1M worth of energy to be spent competing and (2) $1M worth of energy is comparable across markets in a way that 1M kWh is not it is easy to see why paying proof-of-stake validators doesn’t actually create any energy efficiency. Society didn’t use less energy as a result of the Merge. Proof-of-stake is just proof-of-hide-your-work.

As I’ve written about before the externalities of proof-of-work are also much more benign than the externalities of proof-of-stake. Proof-of-work subsidizes the creation of cheap energy (good for society), proof-of-stake increases the competition for scarce capital (bad for society). The direct effects of proof-of-stake are less useful and the indirect effects are more damaging.

So to return to your question …

"Question I’m curious for your take on: does the successful merge of proof of stake show that the approach at least 'works'? It has obvious problems with centralization, but maybe there are still a lot of use cases where centralization is fine?" — AK

The Merge was a huge accomplishment. It eliminated an enormous amount of execution and implementation risk and it moved many major design risks from theory to practical experiment. Proof-of-stake has been significantly de-risked compared to where it was when I wrote Proof of Stake will not save us.

On the other hand it is still too soon to say whether the Merge has introduced fatal centralization risks and it has not changed any of my objections to the fundamental design of proof-of-stake systems. I remain bearish on proof-of-stake generally and on Ethereum specifically. Your mileage may vary.

Other things happening right now:

Today is the 12 year anniversary of the coining of the word shitcoin:

Lido is not a single validator but a consortium of validators working together. Reasonable people can disagree about how much of a control point that represents in practice.

Whether it actually is decentralized enough to resist nation states remains to be seen.