Don't invest in decentralized startups

[Originally published on TheoryOfSelf.com]

A few weeks ago I wrote about why I don’t think it’s wise to hold altcoins. Today I’d like to continue my contrarian impulses by talking about why I don’t think it makes sense to invest in an ICO or startup based on a decentralized application. Decentralized applications (dApps) may very well change the world — but they are very unlikely to make their creators rich. To understand why, it’s helpful to take a step back and understand the basic mechanism that allows entrepreneurs to accrue wealth in the first place: the firm.

Where does shareholder value come from?

Profit is not an automatic side-effect of building a compelling product or having a large customer base. The cotton gin, for example, revolutionized the economy of 19th century America but it never made Eli Whitney rich. It is entirely possible to build a widely used and valuable technology without ever accumulating wealth. That’s because a firm’s profit isn’t based on how useful the technology it builds is, but is instead based on how easy or hard it is for competing firms to enter the marketplace. The easier it is for a new entrant to solve the same problems you are solving, the harder it will be to charge a premium for your products or services.

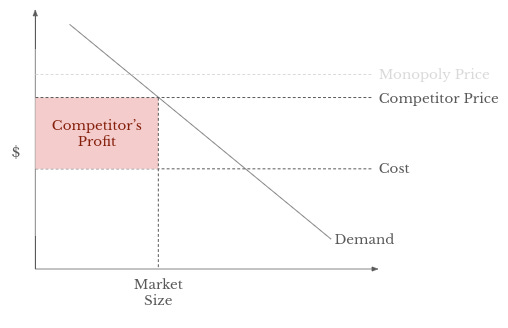

There are a few things we can reason as being true for nearly every firm in nearly every market: if the good/service a firm produces is priced more cheaply demand will go up, and there exists some minimum cost-per-unit that the price cannot fall beneath or the firm won’t be able to cover its costs. Visually economists represent these constraints like this:

A monopoly firm that faces zero competition has the freedom to choose any price it wants for it’s products and will obviously choose the price that results in the greatest possible profit — this premium price will sell fewer units on average but will make up for it with a large profit margin on every item. This is how that looks on our graph:

The green area above the cost line represents profit (or to an economist, rent) and is the source of the wealth that accrues to the owners of the company. A nice situation if you can arrange it! But what happens if someone else enters the market? Knowing they are too late to charge the monopoly price, they will undercut it by just enough to steal all of the first company’s customers (and create a few new customers interested in the lower price point) while still maintaining a healthy premium of their own.

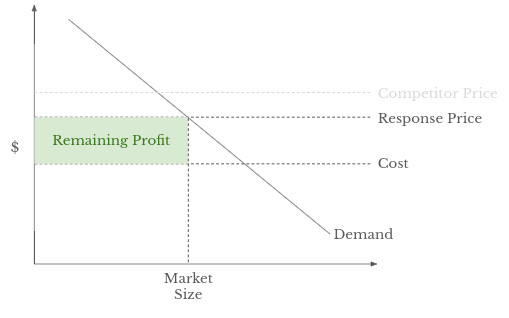

But the first company’s hands are not tied. They, too, can undercut their competitors price, once again reducing the available profit margin, increasing the size of the market and taking back all the customers.

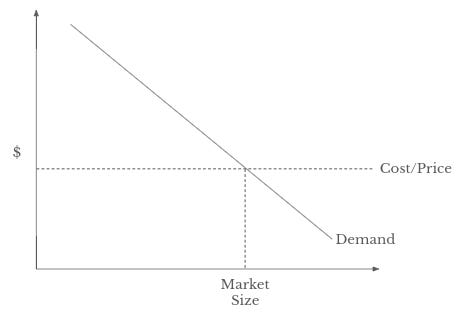

Left unchecked, competing firms selling the same goods or services eventually push the price down to the marginal cost. Economists call this perfect competition. It’s great for consumers — but it chips away at all the available profit that the firms were trying to capture for shareholders.

Markets that are easy to start a business in (hairstylist, laundromat, convenience stores, etc) tend to be competitive. Successful businesses in these markets can make enough money to pay their owner a living wage but they tend not to be the kinds of businesses that make anyone rich because if you were able to charge enough of a premium to get rich from it would invite competition and drag down the price. That’s why Eli Whitney couldn’t make any money from the cotton gin — it was so simple to copy that he couldn’t stop others from making them and undercutting his price. [1]

When assessing how lucrative a business might be for it’s owners / investors, one should start by assessing how competitive the market it seeks to enter is. How easy is it for someone else to solve the same problem the business is solving? The easier it is to create the competition, the harder it will be to charge a premium for the product. Even a product that everyone ends up using might not make you rich.

So what does all this have to do with dApps?

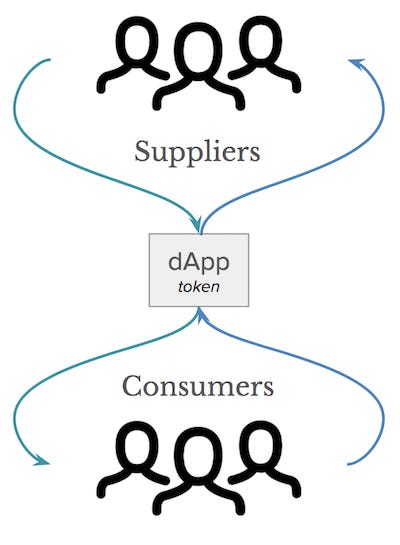

A typical dApp ecosystem is a marketplace connecting buyers and sellers. In Ethereum for example this marketplace connects consumers seeking to run smart contracts with suppliers willing to validate them. For a hypothetical dApp that looks something like this:

As demand for the services provided by the dApp increases, so does demand for token — theoretically providing outsized returns to investors and early adopters who hold token. A nice situation if you can arrange it! But just as with the monopoly firm above, it’s vulnerable to competition. If there are interesting profits for the original holders of token to capture, those profits will attract competition.

In fact it’s even worse for dApps because in order to be decentralized they have to be open source — essentially giving away their core IP for free. That means it’s incredibly easy for a potential competitor to download the dApp codebase, fork it into a new dApp′ with a new token′. Just as above the new dApp′ can underprice the original system, reducing the profit margin and stealing the consumer and supplier bases, since they have no loyalty to the original system beyond the service it provided.

The effort to release a clone of an existing dApp is so cheap that we can expect many of them to be released — some likely just hobby projects produced by the community with no profit motive at all. In fact of one of these hobbyists is likely to port your project over to operate with whatever the dominant store-of-value token turns out to be (in my opinion, likely Bitcoin).

In other words as soon as a dApp’s token begins to appreciate in value, its own community will work to obsolete it by replacing it with a token that does not siphon value off for the dApp shareholders. dApp creators can’t extract wealth from their ecosystems for the same reason that Jimmy Wales can’t charge a premium for Wikipedia. They don’t have any control over the product.

Why are people still building dApps?

Many of the people involved in the cryptocurrency space today are technologists, not economists. The Silicon Valley tradition of consumer application development takes as gospel that if you capture a sufficiently large user base monetization will naturally solve itself. So a decent subset of those building dApps are likely optimists who have not realized the difficulty of extracting value from a system over which you by definition have no control. Others are perhaps idealists who are motivated by a desire to contribute for reasons other than profit such as status or to support the community.

Unfortunately, the lion’s share seem to be dishonest actors who seek to create the illusion of value and then sell that illusion to others who lack the sophistication to recognize that shares in a traditional company and tokens in a decentralized application are fundamentally not the same. They seek to extract wealth not from the eventual consumers of the dApp services, but by unloading their worthless equity onto the greater fools before the system has developed enough to attract the competition that will inevitably destroy it.

Are all cryptocurrency startups doomed?

Not at all. There are lots of workable models for capturing shareholder value for a business that involves crypto. Exchanges like Coinbase and Gemini provide on/off ramps from crypto to fiat. Others like Poloniex and Shapeshift provide crypto-to-crypto access. Organizations like Blockstream seek to build common infrastructure and then sell consulting services to businesses seeking to leverage those tools, akin to the business model of RedHat. There are start ups building tools to help customers store, accept, hide and/or track cryptocurrency — or help you rebalance an indexed investment. All of these can potentially be very lucrative businesses — but the value they seek to create and capture is adjacent to the decentralization rather than on top of it. If your value generation takes place on-chain, it is decentralized. If it is decentralized, you will not be able to use it to extract economic rent.

In short, friends don’t let friends buy appcoins.

[1] Note that stronger patent protections (had they existed) would have given Eli Whitney a legal monopoly and allowed him to enjoy the kind of profits we would expect if he were to invent something similarly significant today.